A new chance for an old problem: the Iranian nuclear deal and European diplomacy

Oleksandr Buriachenko

EPA-EFE/ABEDIN TAHERKENAREH

EPA-EFE/ABEDIN TAHERKENAREH

Iran's political system

To understand the domestic political context, it is worth starting with a general description of the existing power vertical in Iran.

The head of state is the Supreme Leader or ‘Rahbar,’ who is elected by the Council of Experts, which currently consists of 88 members. This body, in turn, is formed by direct vote of all citizens who have reached the age of 15. Legally, the Council of Experts was created to control the activities of the head of state and can vote for his resignation if he fails to cope with this role. However, this has never happened before.

All candidates for this body must be vetted by the Council of Guardians for their knowledge of Islamic norms, suitability for the position, etc. The Supreme Leader appoints half of the members of the Council of Guardians, and the other half is appointed by the Supreme Judicial Council, whose chairman is also elected by the Supreme Leader. Thus, the head of state has a decisive influence on the future composition of the body and the appointment of his successor.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has been the Supreme Leader since 1989. Ayatollah is not a state but a religious term, meaning the highest title of a Shiite theologian who has the right to issue fatwas. The Supreme Leader is not required to be an ayatollah. Khamenei's power is extremely extensive, but not unlimited. Among his most important powers are:

Appointing the commander of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps). These are elite units, separate from the regular armed forces, tasked with protecting the Supreme Leader, the constitutional order and the Islamic Revolution;

Appointing the commander-in-chief of the armed forces;

Appointing the head of the judiciary;

Appointing the head of the state television and radio company;

Appointing the highest-ranking generals and commanders;

Approving the president's candidacy after elections and signing the president's resignation upon the recommendation of parliament or the Supreme Court;

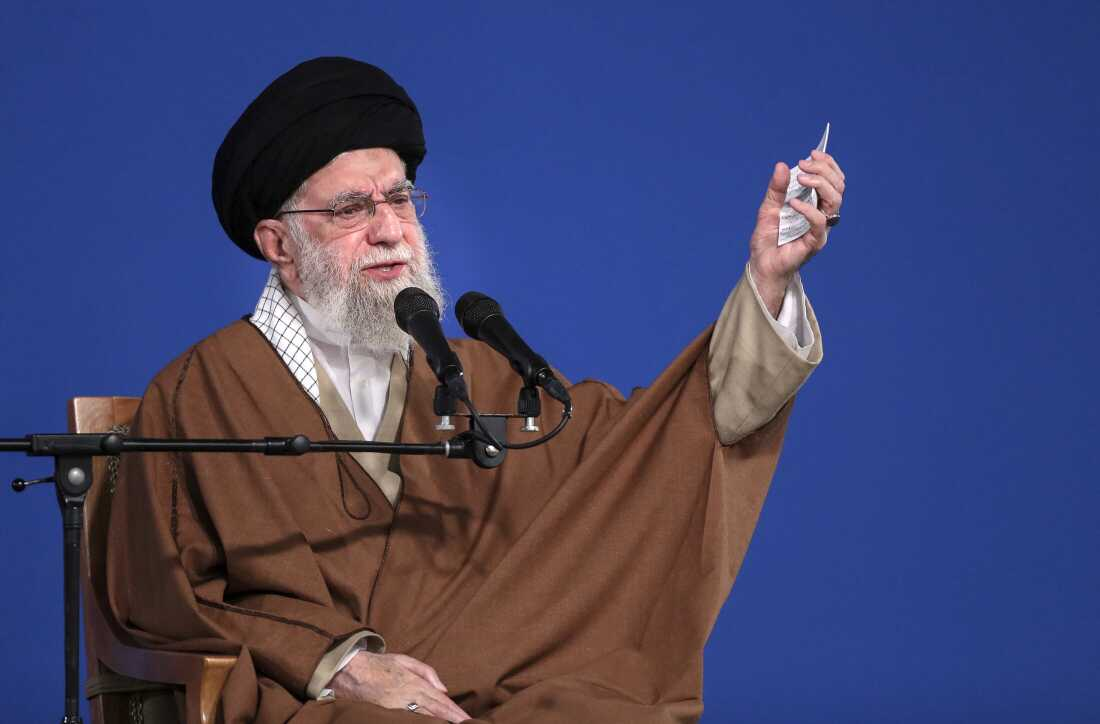

Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Photo AP

Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Photo AP

Thus, the Supreme Leader has control over the country's religious community, security forces and information. In addition, he has significant economic leverage through companies affiliated with the ruling elite. These include, for example, large construction companies with tens of billions of dollars in turnover.

The President of Iran is also an influential figure, but he is always in the shadow of the Supreme Leader. He heads the government — the position of Prime Minister in the country has long been eliminated. The President is elected in elections that are usually more or less fair, but candidates are vetted by the above-mentioned Council of Guardians. This allows the Supreme Leader to filter out unwanted candidates and influence the outcome.

The president forms the cabinet, manages the economy, heads the National Security Council, and is responsible for the implementation of laws and the budget, as well as the work of the state apparatus. However, any strategic decision (defence, security ministers, main directions of foreign policy) is subject to the approval of the Supreme Leader. Therefore, the practical weight of the president depends on the extent to which his views and team correspond to the will of the rahbar - and on the latter's willingness to interfere in executive affairs.

The current president is Masoud Pezeshkian Pezeshkian, who is considered moderate compared to Khamenei and other influential officials. He ran alongside five conservative candidates and won unexpected victory in 2024.

The difference in views: The Supreme Leader and The political elite

Supreme Leader Khamenei's position has not changed for many years. The images of the United States and the ‘Zionist regime’ as the main enemies remain relevant today. After the US withdrew from the nuclear agreement with Iran in 2018 during Donald Trump's presidency, Tehran clearly chose the path of accelerating uranium enrichment and increasing its autonomy. Tehran's negotiations with Washington have continued in recent months, as Iran needs economic improvement, which is impossible without lifting at least some of the sanctions. Economic problems are the key reasons for the protests, which will be discussed further.

Despite this need, Iran has taken a fairly tough stance: it has agreed not to pursue nuclear weapons, but has categorically refused to stop enriching uranium. The Iranian Foreign Minister stated in the context of the new nuclear agreement with the United States:

‘No nuclear weapons - there is an agreement, no enrichment — there is no agreement.’

It is obvious that such rhetoric was approved by the Supreme Leader.

The United States, on the contrary, demands that Iran stop enriching uranium. Previously, the United States wanted to discuss the missile programme, but it appears that the parties have reached a consensus on its taboo, as it is a direct threat to Iran's national security. In the context of the enriched uranium issue, Washington proposed transferring the existing stockpile to the Russian Federation. From there, the necessary material for peaceful nuclear energy in Iran could be supplied. Tehran predictably rejected this idea, as it undermines national pride. What country would agree to voluntarily give up a strategic asset just because another state wants it to? Another idea was to create an international consortium for uranium production involving Iran, the United States, Saudi Arabia and other Arab states. This proposal was not properly discussed due to the outbreak of hostilities, so it may be considered in the future.

The president's position is different. Masoud Pezeshkian, the first moderate reformist president in eight years, proclaimed a course ‘For Iran’ – to revive the economy, weaken isolation and give people more freedom. His victory showed society's demand for change. Pezeshkian directly linked the way out of the crisis to the normalisation of foreign relations: in a televised debate, he said that 40% inflation cannot be overcome without lifting sanctions, and this requires ‘a less confrontational approach in international affairs’. He also stated that the country had driven itself into an ‘economic cage.’ Thus, the new government set a course for reviving dialogue with the West.

President of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian

President of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian

However, the Supreme Leader remains a restraining factor. Despite allowing negotiators to work, he also sets the limits of compromise. His congratulations to Pezeshkian on his victory are telling: Khamenei praised the high turnout and ‘advised continuing the policy of Raisi (the former conservative president),’ effectively warning the new president against making any sudden changes. Therefore, diplomats must balance the demands of reality with the pressure from the ‘hawks’ in Tehran.

There are also pragmatists in power in Iran — something between Pezeshkian and Khamenei. They prefer to reach an agreement, as it is the ‘lesser evil’ compared to economic collapse or a riot of citizens. These include, for example, Foreign Minister Abbas Arakchi and Khamenei's adviser Ali Shamkhani. Both are not shy about making harsh statements against Iran's enemies, but they also advocate negotiations.

A Reuters article quotes two unnamed officials to say: ‘The country is like a gunpowder barrel, and further economic tension could be the spark that ignites it.’ These sentiments are pushing government officials to actively seek compromises.

We should not forget the great risk for supporters of rapprochement with the West - to conclude a ‘bad deal’ and lose support at home. Government officials understand that if Iran receives humiliating conditions such as a complete shutdown of uranium enrichment or restrictions on its missile programme, it could spell political death for the reformists. Because of this, they also have pretty tough demands – lifting some sanctions, guarantees that they won't be reimposed, and keeping the right to peaceful nuclear energy (enrichment). Foreign Minister Arakchi stressed, ‘We can't give up our vital interests just because Trump wants us to do so.’

The paths of Iran and Europe today

Iran's contact with the West is mainly viewed through the prism of its relations with the United States. However, Europe has played and continues to play an important role in negotiations with Iran and has its own rich history of relations with it.

European-Iranian relations can be summarised as ‘complicated.’ The Islamic Republic has been in contact with Europeans for many decades, but serious dialogue on the nuclear issue began in 2003 with the ‘Euro Three’ (France, Germany, and Britain). President Khatami developed dialogue with the EU in 1997–2005 (remember the 2004 Paris Agreement, where Iran temporarily suspended enrichment in exchange for promises of technology). President Ruhani and Foreign Minister Zarif also emphasised in 2015 that Europe played a constructive role in reaching the nuclear agreement during Obama's presidency.

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi greets his counterparts from Germany and the United Kingdom. Handout / German Federal Foreign Office / AFP

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi greets his counterparts from Germany and the United Kingdom. Handout / German Federal Foreign Office / AFP

The American and Israeli strikes have severely, and perhaps irreversibly, undermined Iran's trust in the collective West. This mainly concerns the United States, but the shadow also falls on European countries that are allies of the United States. Moreover, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz stated: ‘We have no reason to criticise what Israel started in Iran a week ago, just as we have no reason to criticise what America did there last weekend.’ Such words are also not contributing to further dialogue with Iran.

The war has also had a serious impact on the positions of reformists. Their arguments about the need for dialogue with the West now seem completely uncertain. This is understandable, because it is difficult to trust a party that can launch missile strikes on your nuclear facilities at any moment. However, there is an option to strengthen the influence of moderate civilian officials. After a brief war with Israel, many top military commanders were killed. New people were quickly appointed to their positions, but this still creates a power vacuum that reformists may try to fill. Only time will tell if they succeed.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is the biggest opponent of the status quo and normalisation of relations with the West. This structure was created as a counterweight to the regular armed forces after the victory of the revolution in 1979. The Corps has one of the biggest stakes in the confrontation with the United States and its allies, as it has numerous business connections and interests supported by its security apparatus. It also retains considerable influence in the political sphere, as it has the crucial mission of preserving the regime.

The IRGC views any nuclear deal as a temporary option to overcome urgent needs by making certain concessions and lifting some sanctions. Commander Hossein Salami, who was killed on 13 June 2025 as a result of Israeli strikes, had stated shortly before: "Our war with America is a war of faith and a battle between oppression and justice, and even if we reach an agreement on the nuclear issue or the war in Gaza ends, our war with Israel will not end, because this war is being waged for existence and faith."

Members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). APA/AFP/afp/STRINGER

Members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). APA/AFP/afp/STRINGER

In addition, Iran still wants to reach some kind of agreement. In March-April 2025, even before the Israeli strikes, Reuters , referring to Iranian officials, indicated that the country desperately needed sanctions relief to improve its economic situation. For context: inflation in Iran is around 40%; every month there are dozens and hundreds of strikes by workers, especially truck drivers, due to rising fuel prices; the budget deficit is around $40 billion. Oil sales are helping to cope with the situation, but if prices fall, the quality of life will decline even further.

Because of this, Europe looks like a better candidate for an agreement. The EU and individual countries have imposed numerous sanctions on Iran, the lifting of which would greatly benefit it. Deep distrust of the US and the need to overcome the crisis may also contribute to rapprochement. The EU can also guarantee an agreement with the US — for example, through a mechanism in which European banks buy Iranian oil for euros, or in which European peacekeepers participate in the inspection of certain facilities, etc.

In addition, rapprochement with the old continent could be a tool for ending international isolation. In fact, Iran has become part of the ‘axis of evil’ alongside Russia, North Korea and other countries. This status is obviously not acceptable to Tehran, as the country has never had positive relations with Russia. The current partnership is rather situational and temporary, as the two states have common enemies.

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and Russian President Vladimir Putin

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and Russian President Vladimir Putin

A preliminary conclusion can be made that the positions of the reformists are currently under threat. They may be improved as a result of the power vacuum created by Israel's attacks or as a result of the transfer of power from Khamenei. This crisis moment should come pretty soon, because the Supreme Leader is already 86 years old and his health isn't the best. This, in turn, could lead to a closer relationship with Europe. We'll talk more about the scenarios further.

What will happen?

A strong rapprochement with the West is currently only possible if there are urgent economic needs. If this is not the case, Ayatollah Khamenei will not give his consent, as relations and trust have been severely undermined by the recent war. Likewise for strengthening the position of reformists, the most favourable conditions for improving relations with Europe and the West will be available after the transition of power.

A change of leadership in authoritarian countries is always a very turbulent moment. In the Islamic Republic, the transition of power has only taken place once, in 1989. At that time, there were ideas about the possibility of moving from the sole rule of the head of state to the creation of a collegial body. This was not finally realised, and Ayatollah Khamenei took the post of Supreme Leader. However, during his reign, Iran has seen a consensus-based approach to decision-making. The Ayatollah coordinates and balances between the branches of government, security forces and the religious community, but he has the final word. None of these centres of influence has a bigger advantage over the others.

It is obvious that after the death of the current leader, the distribution of power will begin. This could lead to the rise of both reformists and conservatives. The following scenarios for the development of relations with Europe and the situation within Iran can be identified:

Bad. In Iran, the conservatives and security forces from the IRGC gain ultimate power. Relations with the West are perceived as toxic, ties are cut, and the country turns even more to the East and intensifies the creation of nuclear weapons to ensure security. The military ignores the economic problems of the population and suppresses protests by force. Dialogue with European countries is suspended, as they are perceived as puppets of the United States.

Moderate. Iran is forced to compromise and reach an agreement with the United States and Israel due to internal economic problems. However, in order to reduce the influence of the United States, Iran seeks to involve European countries in the process. They can be mediators or guarantees of the agreement's implementation. Over time, their importance may grow. If this process is successful, the reformists' positions will strengthen.

It is worth remembering that this scenario is only possible if Europe has strategic autonomy and is aware of its position. To a large extent, this depends on the personalities of individual leaders. Currently, French President Emmanuel Macron is the most active and promising in this regard. His country has historically sought separation and independence from the United States.

Positive. Relations with the US remain toxic, and there is also a need for economic recovery, but it is not so urgent. Europe is moving further away from the United States and establishing its own contacts with the world. In Iran, improving relations with the old continent is seen as a way to get out of the crisis, lift some sanctions and diversify international relations. The authorities in Tehran do not like close contact with Russia, so the opportunity to break out of isolation is very promising. Just as in the previous scenario, this scenario will only have a chance of success if Europe takes a proactive position.

If a collegial governing body is created after Khamenei's death, then in this scenario the influence of decent representatives will be preserved, which could lead to a gradual softening of the political regime in Iran.

On the road to Europe or not?

Iran's rapprochement with Europe is a very likely event, but it is too difficult to predict. This process will depend on many factors, the main ones being:

Europe's position: proactive and independent or passive and limited;

The internal balance of power in Iran: will decent reformists or radical conservatives have the upper hand in the near future?

The position and actions of the United States: continued maximum pressure or a willingness to soften its position?

When will the transition of power from Khamenei take place and how will it play out?

The last point can be highlighted as the most important, because Iran is a country where the decisions of the Supreme Leader are crucial. Khamenei's position has long been known, so something new can only be expected from the new government or forces that will gain influence as a result of the transition. Even if Europe is ready for a pragmatic rapprochement, nothing will happen without the agreement of the Iranian leader.

One thing is certain: rapprochement has a chance of happening. Iran is a hostile state towards Ukraine, but it has a chance for change. Diversification of international relations and a partial shift away from Russia will already have positive consequences. We just have to wait and see.