Shadow naval warfare: the consequences of Ukraine's attacks on Russia's oil economy

Denys Klymenko

Photo: Maritime.bg

Photo: Maritime.bg

At first, Russia's actions were limited to President Putin's words at the VTB International Investment Forum, held in Moscow on 2 and 3 December: ‘The most radical way is to cut off Ukraine from the sea, then it will be impossible to engage in any activity at all...’. On 6 December, Russia launched active attacks against Ukraine's logistics infrastructure. Odesa, its energy and port infrastructure, was particularly affected. The shelling of Odesa was especially intense on 12 December. Russian President at the VTB World Economic Forum in Moscow. December 2025, Ramil Sitdikov/Sputnik

Russian President at the VTB World Economic Forum in Moscow. December 2025, Ramil Sitdikov/Sputnik

Russia has maintained oil supplies through legal channels. However, in order to compensate for lost revenue, Moscow has had to supply oil through illegal channels.

Old – does not mean cheap

The People's Republic of China remains the largest consumer of Russian oil, but the main supply of ESPO brand oil via the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline is still insufficient to meet Beijing's needs. Although the price cap applies exclusively to maritime supplies, at peak capacity, ESPO supplies only 50 million tonnes of oil per year to China, while China consumes more than 500 million tonnes annually. In order to continue selling oil at more than $60 per barrel and maintain flexibility in the supply of sanctioned energy resources by sea, Russia has decided to form a shadow fleet. The tanker "Fossil" near the port of Rotterdam. Launched in 2009, it was operated by Greece until 2018. Sold to Russia in 2023, chartered under the Panamanian flag and registered to a Vietnamese company. November 2022, Ger Bauritius/VesselFinder

The tanker "Fossil" near the port of Rotterdam. Launched in 2009, it was operated by Greece until 2018. Sold to Russia in 2023, chartered under the Panamanian flag and registered to a Vietnamese company. November 2022, Ger Bauritius/VesselFinder

The formation of a shadow fleet almost always follows the same formula: the cheapest possible ship is purchased and chartered under the flag of a country with a large register and convenient legislation in terms of transparency and taxation (usually Panama or Liberia). The ship is registered with the owner under a fictitious company in an offshore zone, mainly the UAE. Insurance is rare, as Western insurers usually refuse to work with the Russian fleet, so the ship is serviced by fictitious companies or Asian insurers. This is done not for the sake of risk coverage, but to avoid questions during inspections in ports or straits. The most popular class of ships in the shadow fleet is "Aframax", with a deadweight of up to 114,000 tonnes and a draught of about 15 metres, which allows them to pass through straits with no limitations.

However, this fleet now has one significant feature that was not previously characteristic of it: atomisation. In 2022, the shadow fleet was formed almost entirely under one scheme, which involved a large company. For example, in 2022, the company "Gatik Ship Management", registered in Mumbai, appeared in the Indian registers. Its fleet grew sharply to about 60 vessels. Although it was not the owner on paper, it was the de facto owner due to its status as the operational and commercial manager of the ships.

In 2023, the Financial Times published an investigation revealing that the company was a dummy company involved in transporting sanctioned Russian oil to India. By 2023, ships registered with "Gatik" had transported about 83 million barrels of oil, most of which belonged to Rosneft. That same year, the company was hit with sanctions: the American Club refused to insure its ships, St. Kitts and Nevis removed 36 ship flags, and the British Lloyd's List registry removed 21 ships from its lists. That same year, ships began to be actively renamed and registered to new companies. The tanker "Qendil" (IMO 9310525), attacked on 19 December 2025, was operated by this Indian company.

Since the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea does not allow ships to be seized in international waters, ship-to-ship (STS) transshipment is now more commonly practised, saving Russia time and resources in energy deliveries. The second benefit of transshipment is that it automatically hides the oil, as it is diluted in the tanker. A popular transshipment area is the international waters of the Mediterranean Sea. The most popular route is from the Baltic Sea (the 1857 Copenhagen Convention classified the straits as international waters) along the northern coast of Russia to China or through Gibraltar to the Suez Canal, if oil needs to be delivered to India. Sometimes oil is mixed in offshore ports such as Oman, especially its ports of Sohar and Fujairah.

Although the Strait of Gibraltar is narrow enough that Spanish territorial waters completely block it, the legality of the ship's arrest is questionable. Firstly, UNCLOS prohibits the obstruction of ships' transit through straits under Article 44. Secondly, there is the question of who carried out the seizure – both Spain and the United Kingdom claim sovereignty over the strait. The conflict continues to this day in connection with the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, which gave London indefinite sovereignty over the strait, but Spain claims that the treaty only gave Britain the land. A precedent for this was the seizure of the Iranian tanker "Grace 1" by the British Royal Marines, but this case was rather exceptional due to the proven violation of EU sanctions by the tanker and the ship's detention.

The Russian shadow fleet is unreliable, with ships often having defects that are recorded during inspections. Despite the fact that the oil is subject to sanctions and is usually transported by old ships that should have been decommissioned or sent for scrap, the Russian Federation sells this oil at higher prices. Although Asian consumers pay more than $60 per barrel, they receive oil on spot terms, pay in their own currency or roubles, do not need to integrate into the bureaucratic apparatus of Western countries, and do not have to use the services of Western insurers. At the same time, they are at risk of secondary sanctions, so oil consumers such as China are working on the domestic market, having their own schemes to circumvent sanctions.

Forced dumping

Since the unreliability of the ship and the risks involved, ranging from arrest to environmental disaster, along with sanctions, are very serious problems, and prices for commercial ships have jumped after 2022, Russia is forced to sell oil at a discount under these conditions, but usually this discount still allows the final price to be higher than $60 per barrel.

To avoid sanctions, China, the main consumer of Russian oil, managed to come up with its own scheme to bypass them – a system of oil refineries controlled by the government but separate from the ‘big four’ state-owned oil and gas companies of the PRC. The media began to refer to them as "teapots", but China uses the euphemism “地炼”, which literally translates as "local oil refinery". The lion's share of these are located in Shandong Province on the coast of the Yellow Sea, not far from major Chinese industrial centres.

Teapots import oil from Russia and Iran and operate in the domestic market of the PRC, refining this oil and selling the finished fuel to Chinese consumers. Accordingly, secondary sanctions do not threaten them. They import oil at prices above the established limit, which brings Russia higher revenues, and transshipment from Russian tankers to Chinese ones in open waters prevents these ships from being seized. In the context of the war with Russia, Ukraine is taking advantage of the opportunity to cause irreparable damage to these schemes, as it is in Kyiv's interest to weaken the Russian economy, which is dependent on oil exports.

UAV attack by the SBU on Lukoil's oil production platform in the Caspian Sea. December 2025. SBU

UAV attack by the SBU on Lukoil's oil production platform in the Caspian Sea. December 2025. SBU

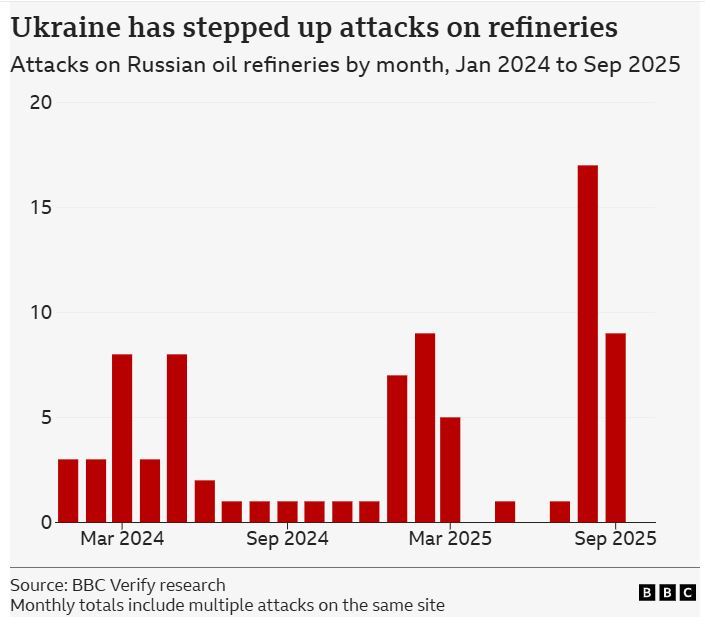

Ukraine started attacks against Russian oil infrastructure at the start of the full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022. These strikes were isolated and mainly in border areas, such as the Belgorod and Rostov regions. However, they only became systematic in 2023 due to the possibility of their technical implementation, the tightening of EU and US sanctions against Russian oil, and, indirectly, Russia's withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Agreement in July of that year. Although it is impossible to confirm whether there was a kind of ‘deterrence through refusal’ before Russia's withdrawal from the grain agreement (since attacks on Ukrainian grain and Russian oil became systematic and symmetrical specifically in 2023), it can be assumed that it was in 2023 that both Moscow and Kyiv, having the resources to attack each other's largest economic sectors, resorted to these actions, knowing that a response was guaranteed.

Already in January 2024, UAV attacks took place against oil refineries in Tuapse, Kstovo, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Samara and other regions.

From March to June of the same year, attacks resumed on the same plants, which had been restored after the previous attacks in January.

In February 2025, a gas condensate plant in Astrakhan, operated by Gazprom, was attacked.

In January, the Ryazan oil refinery and several logistics hubs were attacked again.

In July, the strikes resumed: the Ilsky oil refinery in the Krasnodar region was damaged.

In September-October, there were massive UAV attacks on oil refineries, oil depots and pipelines, which reached their peak in November.

In November, the Ukrainian Armed Forces launched their first attacks on the Russian shadow fleet. Between 28 November and 10 December, three tankers were attacked in the Black Sea: ‘Kairos’, ‘Virat’ and “Dashan”, as later confirmed by the Main Intelligence Directorate and the Security Service of Ukraine. The circumstances surrounding the sinking of the oil-filled tanker "Mersin" off the coast of Senegal are unknown. Despite Russia's claim about an attack on the "Midvolga-2" tanker, which, according to media reports, was carrying sunflower oil to Georgia, Ukraine denied any involvement in both incidents.

In November, the Ukrainian Armed Forces launched their first attacks on the Russian shadow fleet. Between 28 November and 10 December, three tankers were attacked in the Black Sea: ‘Kairos’, ‘Virat’ and “Dashan”, as later confirmed by the Main Intelligence Directorate and the Security Service of Ukraine. The circumstances surrounding the sinking of the oil-filled tanker "Mersin" off the coast of Senegal are unknown. Despite Russia's claim about an attack on the "Midvolga-2" tanker, which, according to media reports, was carrying sunflower oil to Georgia, Ukraine denied any involvement in both incidents.

On 11 December, the Security Service of Ukraine carried out its first successful strike against oil platforms. Both were located in the Caspian region – the first at the Vladimir Filanovsky oil and gas condensate field, the second at the Yuri Korchagin oil and gas condensate field. Both fields and oil platforms are operated by the Russian company Lukoil. A day later, on 12 December, the SBU attacked the Filanovsky field again. On 15 December, the attack was repeated against the Korchagin field.

On 19 December, the SBU managed to attack the tanker "Qendil" in the Mediterranean Sea. This tanker was travelling from the Indian port of Sikka to the Russian port of Ust-Luga. However, after the attack, information emerged that Russian GRU General Andrey Vladimirovich Averyanov was on board and died as a result of the strike. According to media reports, he was the head of military unit 29155, also known as the ‘161st Specialist Training Centre’.

Averyanov was believed to be involved in organising the explosions at an ammunition depot in Vrbětice, Czech Republic, the poisoning of former GRU employee Sergei Skripal, and the murder of former Wagner PMC head Yevgeny Prigozhin. Interestingly, after the attack, the ship lost speed and changed course, first to the port of Said in Egypt and then to the port of Aliaga in Turkey. The latter has the world's fourth largest ship recycling yard.

Theoretically, this could be explained by the receiving of a distress signal from Ankara. However, if there really was a GRU officer on board, and the draught of 8.2 m indicates that the ship was probably not completely empty (as claimed by the Ukrainian media), then it is likely that it was carrying cargo that was undesirable to fall into the wrong hands. Despite the fact that Gibraltar is a transit zone that guarantees free passage for ships and UNCLOS does not fully apply there, according to Article 221 of the Convention, Spain or Britain have the right to "take measures proportionate to the threat to the coast", and such a threat exists in the form of water pollution. The narrowest point of the strait is about 8 nautical miles, while territorial waters extend 12 miles from the coast.

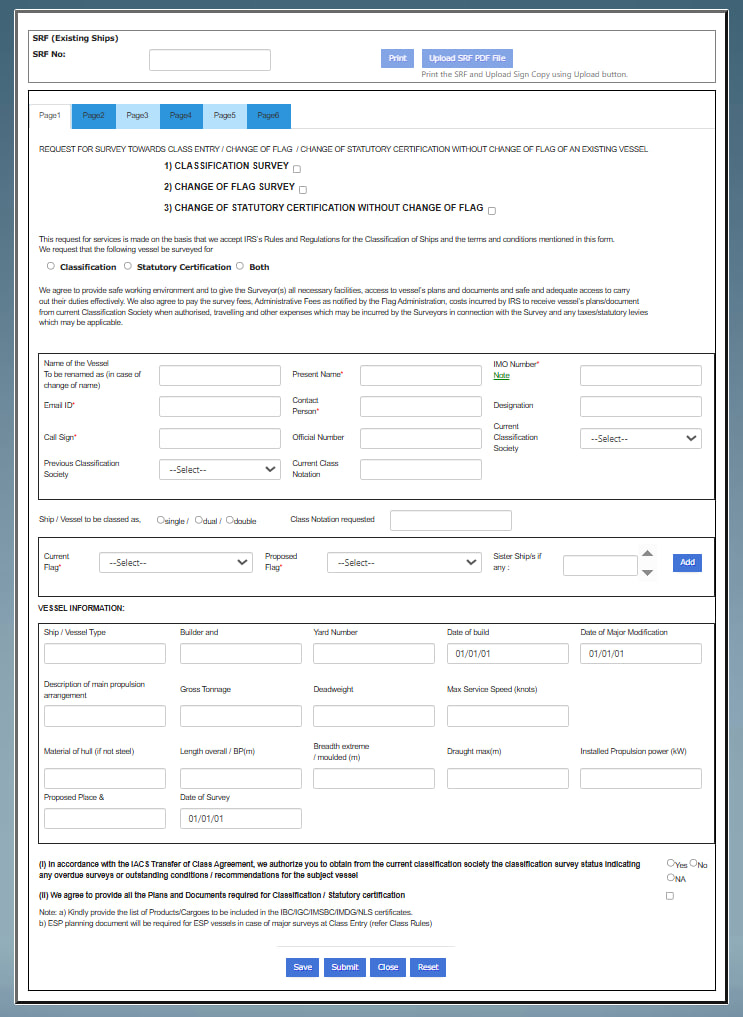

A questionnaire that the ship owner/manager must complete to obtain a ship classification in the Indian Register (IRClass). Even if a ship is under sanctions, classification allows it to enter ports in countries that have not joined the sanctions. The ship "Qendil" was classified in this register back in 2021, and even after the sanctions, it was not removed from it

A questionnaire that the ship owner/manager must complete to obtain a ship classification in the Indian Register (IRClass). Even if a ship is under sanctions, classification allows it to enter ports in countries that have not joined the sanctions. The ship "Qendil" was classified in this register back in 2021, and even after the sanctions, it was not removed from it

Russia can only resort to such radical action through a ‘salami tactic,’ i.e., gradual small attacks, so that the escalation is not so rapid and does not cause a deterioration in relations with other states. While the attack on the Turkish cargo ship "CENK T" in Odesa appeared to be accidental, the attack on the Turkish tanker "VIVA" in the Black Sea was targeted. So far, this is the second attack by the Russian Federation against commercial shipping in the open sea (the first occurred in September 2024 against the bulk carrier AYA). Russia has not confirmed its involvement in this, but the Russian media has begun to justify the attack as a response to the Midvolga-2. For example, the russian publication "Lenta" mentions the attack in the context of previous attacks on ships by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Of all five recent incidents involving Russian ships, the Midvolga-2 was the only ship with a Russian flag.

Ukrainian-style game theory

The current situation resembles bilateral brinkmanship, i.e. mutual attempts by Moscow and Kyiv to exert pressure during negotiations mediated by the United States. The Russian Federation's shadow fleet is a grey area that Russian propaganda is unable to exploit publicly (except for repeating the narrative of ‘terrorism on the part of the Armed Forces of Ukraine’), and this strategy is quite effective against the Russian economy, but moderately limited.

It is important to assess the risks not only from Russia, but also from third parties, which are already occurring. First of all, all three attacked tankers were already empty, judging by their draught – a direct indicator that Ukraine is not ready to escalate the situation. An attack on a full tanker would provoke a sharp escalation on the part of the Russian Federation (including intensified attacks against Ukrainian bulk carriers openly; or symmetrical attacks against empty Ukrainian bulk carriers), the possibility of an environmental disaster with an oil spill in the closed waters of the Black Sea region, and condemnation of Ukraine by other states, as the entire Black Sea region would be at risk. This does not play in Kyiv's favour, so attacks against empty tankers and, as a priority, the shadow fleet remain the most rational options for Ukraine. The attacks themselves already have a side effect for all countries in the region: between the beginning of November and 12 December, the price of insurance in the Black Sea region rose from 0.25-0.3% to 0.5-0.75% of the ship's value, i.e. almost threefold. The Russian shadow fleet tanker "Kairos" near the port of Ahtopol, Bulgaria. It was attacked in international waters and towed by a Turkish ship to Bulgarian territorial waters, after which it ran aground. December 2025. Zdravko Vassilev/AP Photo

The Russian shadow fleet tanker "Kairos" near the port of Ahtopol, Bulgaria. It was attacked in international waters and towed by a Turkish ship to Bulgarian territorial waters, after which it ran aground. December 2025. Zdravko Vassilev/AP Photo

Ukraine is currently in a state of ‘escalation dominance,’ where it has more options for escalation, but so far the most risky and acceptable option for it is to attack a tanker filled with oil in the open sea with subsequent possible ‘plausible deniability.’ The Russian Federation does not have such capabilities, as every attack against a commercial ship carries geopolitical risks.

Russia's attacks against the energy sector are ineffective, the losses of the Russian Black Sea Fleet make the blockade of Black Sea ports physically impossible, and attacks on bulk carriers are very damaging to Russia itself, as Ukraine mainly uses the services of actors that are ‘untouchable’ for Russia due to its own poorly developed fleet: the UN (supplies under the UN flag are protected by international law as part of tenders for humanitarian aid, such as the ‘Grain from Ukraine’ brand), Turkey (control over the straits: thanks to the 1936 Montreux Convention, Turkey has blocked the passage of Russian Navy ships into the Black Sea, with the exception of the Black Sea Fleet; possible facilitation of arrests of shadow fleets or longer inspections, which will force demurrage payments for downtime, reducing sales margins), Greece (which now often handles legal shipments of Russian oil) and China (an ally of Russia).

Referring to the abovementioned increase in ship insurance prices in the Black Sea region, attacks against the Russian oil economy will also have negative consequences for Ukraine.

Cui bono?

It remains profitable for influential actors to artificially reduce oil production, as there has been a supply glut in the oil market. Production in countries around the world has jumped significantly, demand has grown more slowly than expected, and this has led to a plummet in oil prices. As of November-December, Brent is holding at $60-65 per barrel, and WTI at $56-61 per barrel. To stabilise the market, OPEC+ froze quotas until the end of the first quarter of 2026, but at the global level, this deficit on the part of Russia (the largest since 2022) did not play a significant role. Oil prices did not rise because the market compensated for this with overproduction on its own side.

The temporary removal of such a player from the oil market may allow oil giants to stabilise and try to raise prices in a more stable and predictable market. It is now important for all oil-exporting countries to reach Brent and WTI prices in the range of $70-90 per barrel.

At the regional and local levels, Ukraine will continue its natural gradual escalation, but this does not rule out the risk of attacks on commercial vessels associated with Ukraine, as the "VIVA" precedent has already shown. However, even if such incidents do occur, they will not be so intense as to worsen relations with partners. Against the backdrop of negotiations, Russia remains under pressure to maintain the intensity of hostilities along the front line, which is currently the case. This is the only chance to respond symmetrically to Kyiv and force the Ukrainian government to make concessions in order to end the war and achieve a potential easing of sanctions imposed by Trump in 2022.