Russian literature in Europe: monitoring results

RESURGAM EDITORIAL

While Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine is going on, European publishers and distributors keep translating and importing a wide range of modern Russian literature. At the same time, Russia is systematically using culture, especially literature, as a tool for its soft power abroad. It is therefore critically important to identify Russian authors who both spread Russian propaganda narratives and contribute to maintaining Russia's presence in Europe. These phenomena are dangerous because they can influence Europeans' ability to critically assess Russia's actions and bring it to justice for its invasion of Ukraine.

While Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine is going on, European publishers and distributors keep translating and importing a wide range of modern Russian literature. At the same time, Russia is systematically using culture, especially literature, as a tool for its soft power abroad. It is therefore critically important to identify Russian authors who both spread Russian propaganda narratives and contribute to maintaining Russia's presence in Europe. These phenomena are dangerous because they can influence Europeans' ability to critically assess Russia's actions and bring it to justice for its invasion of Ukraine.

In August and September 2025, the Resurgam community, in collaboration with the Ukraїner project, conducted research on the presence of contemporary literature translated and published in Russia on European markets. The aim was to record the distribution and publication of books by contemporary Russian authors through publishing houses, bookshops, libraries and online platforms, analysing their ideological content and identifying the threats they pose.

We researched four European countries – Germany, France, Great Britain and Spain – which have large book markets and cultural significance in the EU. We combined direct monitoring with in-depth analysis, including OSINT analysis, interviews with the local population, publishing house analytics, etc.

We reviewed major chain and independent bookstores (e.g., Thalia and Dussmann in Germany; Fnac and Cultura in France; Waterstones in the UK; El Corte Inglés and Fnac in Spain), public and university libraries, literature festivals and book fairs (particularly in Frankfurt and Leipzig), as well as online platforms (Amazon, BookFinder, etc.).

The sample included contemporary Russian fiction and socio-political books written after the 1990s. Classical Russian literature, such as Tolstoy, Pushkin, Dostoevsky, etc., was not taken into account due to its deep-rooted influence in European countries.

Research results

Germany: the widest range of Russian literature

Germany has the widest range of translated contemporary Russian literature. Bookshops such as the Thalia chain and Dussmann stores in Berlin stock works by Russian writers of various genres and ideological directions. On the shelves, you can find protest fiction and memoirs by opposition authors, political journalism and even pro-Kremlin texts.

German shelves feature protest dystopias (by authors such as Dmitry Glukhovsky and Vladimir Sorokin), émigré prose (Mikhail Shishkin, Viktor Yerofeyev), analytical works about the regime (Irina Rastorgueva[1] [2] [3] [4] ) and even propaganda books (Sergey Karaganov, Nikolay Starikov). Among the authors are explicit critics of the Kremlin, neutral artists and supporters of imperial ideas. This makes Germany a key platform for observing the full picture of what is currently on offer.

For example, alongside the protest prose of Glukhovsky or Sorokin, there are translations of the book ‘Unholy Saints’ by Metropolitan Tikhon (Shevkunov), which popularises the image of the ‘wonderful Russian soul’ and belongs to the pro-regime segment.

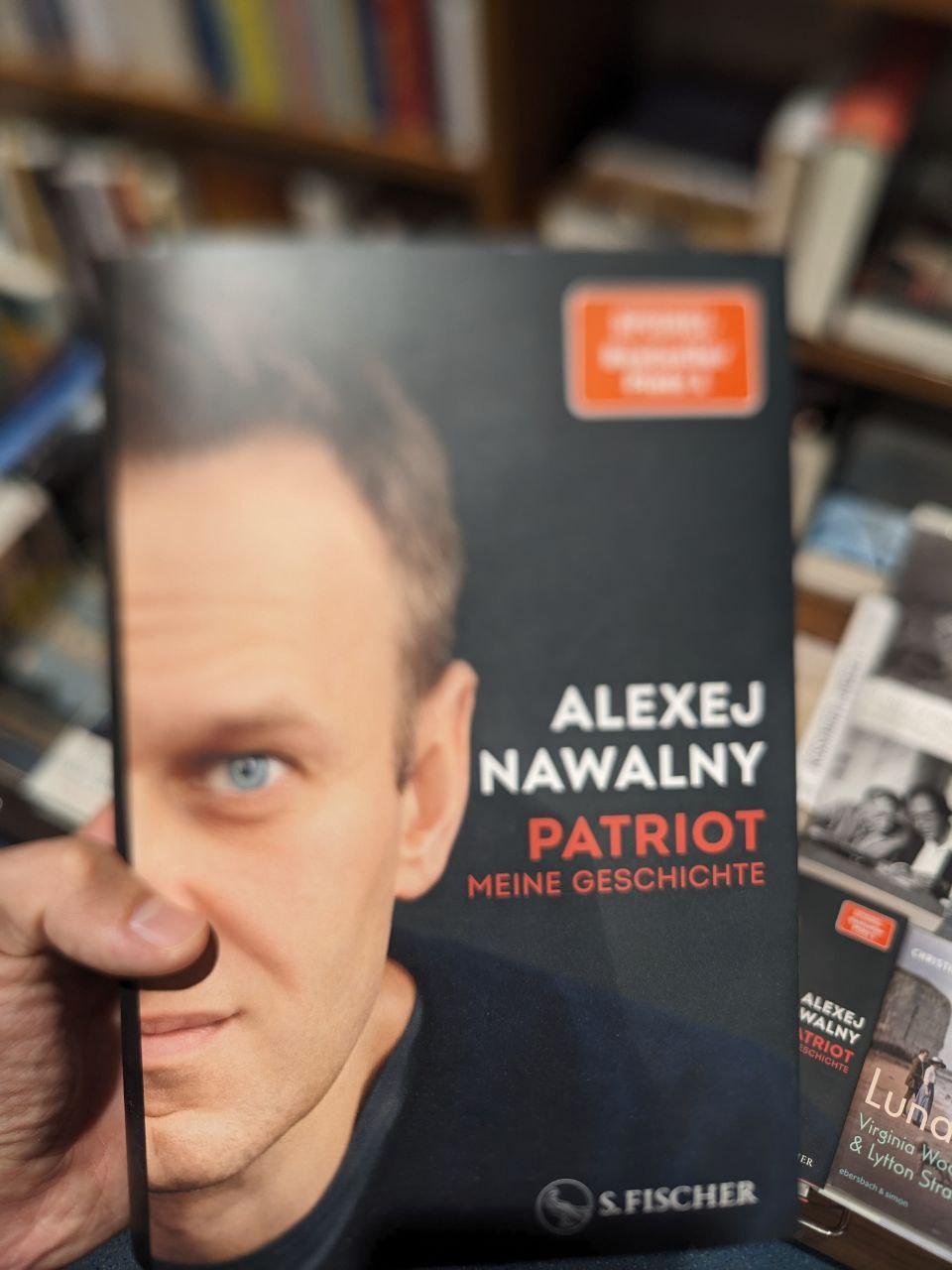

Such a wide range reflects both the sustained interest of German readers in the topic of contemporary Russia and the absence of official restrictions on the import of controversial publications. Examples of Russian "books" available in German bookshops

Examples of Russian "books" available in German bookshops

France: focus on fiction, as well as peripheral political journalism

The French book market gravitates more towards fiction and intellectual prose, shaping the image of Russian literature as a cultural phenomenon. The large chains Fnac and Cultura, as well as Parisian bookshops, stock contemporary Russian novels in French and, less frequently, non-fiction about the current political situation.

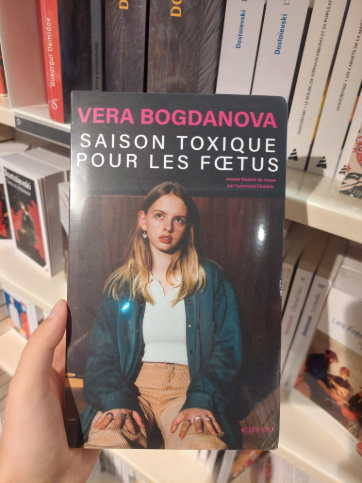

Among the Russian novels in Parisian bookshops were: Vera Bogdanova's ‘The Season of Poisoned Fruit’ by Vera Bogdanova about the 1990s, ‘Number One’ by Mikhail Shevelev about the KGB and the new Russia, ‘Asan’ by Vladimir Makanin about Chechnya, ‘Aifak 10’ by Viktor Pelevin about the digital future, and others. These are mostly books about Russian life, historical memory, emigration, or futuristic plots.

On the other hand, translations of sharp political journalism are rare in France. For example, Navalny's book ‘Patriot’ has not yet been published in French. It seems that French publishers are still cautious about investing in translations of topical political non-fiction, preferring prose and cultural studies. A shelf in a Paris bookshop: Vera Bogdanova's ‘The Season of Poisoned Fruit’

A shelf in a Paris bookshop: Vera Bogdanova's ‘The Season of Poisoned Fruit’

Great Britain: political documentaries and Navalny

In Great Britain, contemporary Russian authors are less diverse and focus on political documentaries and stories/narratives about resistance to the regime. This contrasts sharply with the wider range of genres available in Germany.

British booksellers have emphasised the figure of Alexei Navalny (Banalny). For example, the London bookshop Waterstones had a large display of the English-language edition of Navalny's ‘Patriot: A Memoir’. This book, published posthumously, attracted considerable attention from the British public as ‘the voice of a fallen fighter against dictatorship.’

Other contemporary Russian authors are noticeably less represented. Translations of Sorokin, Glukhovsky or Ulytska are rarely found in large displays, but rather as single copies in specialised shops. The British audience is more interested in finding explanations of contemporary Russia through memoirs, reports and investigations than through fiction. A large display at Waterstones with Alexei Navalny's book ‘Patriot’

A large display at Waterstones with Alexei Navalny's book ‘Patriot’

Spain: a smaller market – greater penetration for propaganda

The Spanish segment of Russian literature is significantly smaller in volume, but it has one notable feature: pro-regime ideological literature in this country is much more likely to be the focus of publishers than in Western Europe in general.

The catalogues of several Spanish publishers feature translations of leading Putinist theorists. For example, the independent publishing house Hipérbola Janus has published the works of Alexander Dugin, the ideologist of the “Russian world”, in Spanish. Another publishing house, Ediciones Fides, has launched a series called “Colección Geopolítica”, which publishes books on geopolitical concepts that are in line with the Kremlin’s narratives. A striking example in our report is the Spanish translation of Dugin's ‘Fundamentals of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia,’ which is distributed in electronic form mainly through online channels and niche media.

Sales of these pro-Russian publications are minimal, but their appearance is alarming. While in Germany or France, “Putinist” literature exists mainly in the form of imported Russian books and is not supported by large publishers, in Spain a certain ecosystem of small publishers has emerged that willingly translates Kremlin texts. This may be due to the historical presence in Spain of anti-American, ultra-left and ultra-right groups, which paradoxically converge on pro-Russian positions.

These publications do not have a wide reach – the mass reader in Spain is more interested in classical Russian literature (Tolstoy, Chekhov) or neutral contemporary bestsellers (such as the novels of Boris Akunin). Contemporary opposition authors (Sorokin, Glukhovsky) have hardly been translated into Spanish, with the exception of Lyudmila Ulitskaya, who was published before the war as a winner of international awards.

We can see that pro-regime Russian literature, probably due to its anti-Western orientation, has found its way to Spanish readers. This means that there is a need to inform Spanish society about the threat of Kremlin disinformation.

Russian non-fiction authors in Europe: a new challenge

Separately, we would like to highlight the emergence on the European market of Russian non-fiction authors who promote imperial and anti-Western narratives disguised as analysts. These are political treatises, historical reconstructions and journalism that justify aggression and the concept of the ‘Russian world’. While propaganda fiction books are quite rare and can be recognised by their content, pseudoscientific treatises are often disguised as serious studies and find their way into libraries and book catalogues.

Alexander Dugin is one of the main ideologists of Putinism and the author of the Neo-Eurasian doctrine. His works, such as ‘The Foundations of Geopolitics’ and ‘The Fourth Political Theory’, justify Russia’s expansion and the elimination of Ukrainian statehood, promoting the idea of an empire disguised as science. In France, his works were translated by Ars Magna, in Spain by Hipérbola Janus and Ediciones Fides, in Germany by right-wing publishers, and in Britain by Arktos Media.

Sergey Karaganov is a Kremlin adviser and strategist who has been calling for nuclear blackmail and forceful pressure on the West for years. He supported the annexation of Crimea and claims in his articles and brochures that only a strike against Europe will ‘save the world from the Western shackles’. His articles have been published in magazines in Spain (El Viejo Topo) and in Germany – collections on the ‘Russian security doctrine’. Formally, this looks like expert analysis, but in reality it normalises the idea of war against Europe.

Leonid Savin is an apprentice of Dugin and a populariser of his ideas. In his books, he promotes the concept of ‘multipolarity’ under Russian leadership, conspiracy theories about ‘Western special services’ and justifies the invasion of Ukraine as a ‘preventive measure’. His translations have been published in Spain (Ediciones Fides) and Britain (Black House Publishing). Savin is an example of how Kremlin propaganda enters Europe posing as alternative geopolitics.

Nikolai Starikov is a publicist and politician known for his conspiracy books. He rewrites 20th-century history, claiming that Hitler was brought to power by the Anglo-Americans and that Ukraine ‘was never a state.’ His books – ‘Who Forced Hitler to Attack Stalin’ and ‘War: By Foreign Hands’ – are sold in major German chains such as Hugendubel and KulturKaufhaus, appear on Amazon and are translated in Latin America. This is an example of dangerous revisionism spreading in the West.

Conclusions

1. Monitoring shows that Russian literature in the West has not disappeared, but has become segmented. There are now clearly visible ‘blue’ (opposition) and ‘red’ (regime) zones. Most major European publishers prefer authors with a clear anti-war stance or ‘neutral classics’ (such as Ulytska). Those associated with Putinism are published in small print runs or not translated at all. This is a gradual isolation of the ‘toxic’ segment. However, complete displacement has not occurred: more than three years after 24 February 2022, the latest Russian books are still on sale. In other words, the demand for knowledge about the ‘soul of Russia’ has not disappeared.

2. European countries have different profiles: Germany maintains the widest range, the United Kingdom focuses on political texts, France presents Russian literature within the framework of high culture, while Spain has proved to be the most open niche for pro-Kremlin pseudo-geopolitics. It is therefore important to plan campaigns to counter Russian soft power with these differences in mind.

3. The European market distinguishes between Russian anti-war or neutral authors and propagandists. In general, this is partly positive for Ukraine. However, such neutral authors, who divert attention from Russian aggression, can influence Europeans' ability to critically assess Russia's actions and hold it accountable for its invasion of Ukraine. It is therefore important to supplement the literary discourse with political context through afterwords, articles and explanations.

4. The most vulnerable spot is the infiltration of Russian ideologues posing as experts. Books by Dugin or Karaganov should not become ‘another perspective’ in university libraries, because they are not an alternative opinion, but a direct threat to the truth.

5. There is a need to work with bookstore chains and online platforms (Amazon, eBay) to remove overtly propagandistic materials on the grounds of ‘hate speech’ and ‘justification of war crimes,’ as well as support for calls to wage aggressive war. At the same time, it is necessary to interact with government agencies and regulators to compile sanctions lists for such literature.

RESURGAM EDITORIAL