INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL

COMMUNITY

+ Join

Support

Danylo Vovchenko, political observer of the Indo-Pacific region, exclusively for Resurgam

The protest escalated into clashes on Whitehall Street. Photo: Getty Images

The protest escalated into clashes on Whitehall Street. Photo: Getty Images

Autumn 2025 in the UK began with one of the largest protests in the country's history amid a worsening social crisis caused by migration.

On 13 September, a violent protest took place in London under the slogan ‘Unite the Kingdom’, bringing together more than 110,000 participants and accompanied by clashes with the police. The demonstrators demanded stricter border controls, a reduction in migration flows and a change in Keir Starmer's government policy, accusing him of 'betraying the interests of the nation'. In contrast to this protest, according to the BBC, around 5,000 protesters gathered in another part of London for the so-called ‘March Against Fascism’.

The protests in London have finally exposed the serious polarisation of British society, which until now had not gone beyond parliamentary debates, private scandals, social surveys or television talk shows. The issue of migration, which has been at the forefront of political discussions over the past decade, has now taken to the streets, posing a serious challenge to the internal stability of the state. The protests demonstrate a deep social division, where migration is no longer purely a social or economic issue, but also a marker of national identity.

The United Kingdom is one of Kyiv's leading allies in the war with Russia, supplying modern weapons, providing financial assistance and acting as a key advocate for Ukraine on the international stage. The question therefore arises: how might internal instability affect British foreign policy?

The September protests surrounding the migration issue were not only the culmination of discontent, but also a manifestation of new features of the protest movement, which has taken on a hybrid character. The origins of this movement can be found not only in current political decisions, but also in long-term social and identity issues.

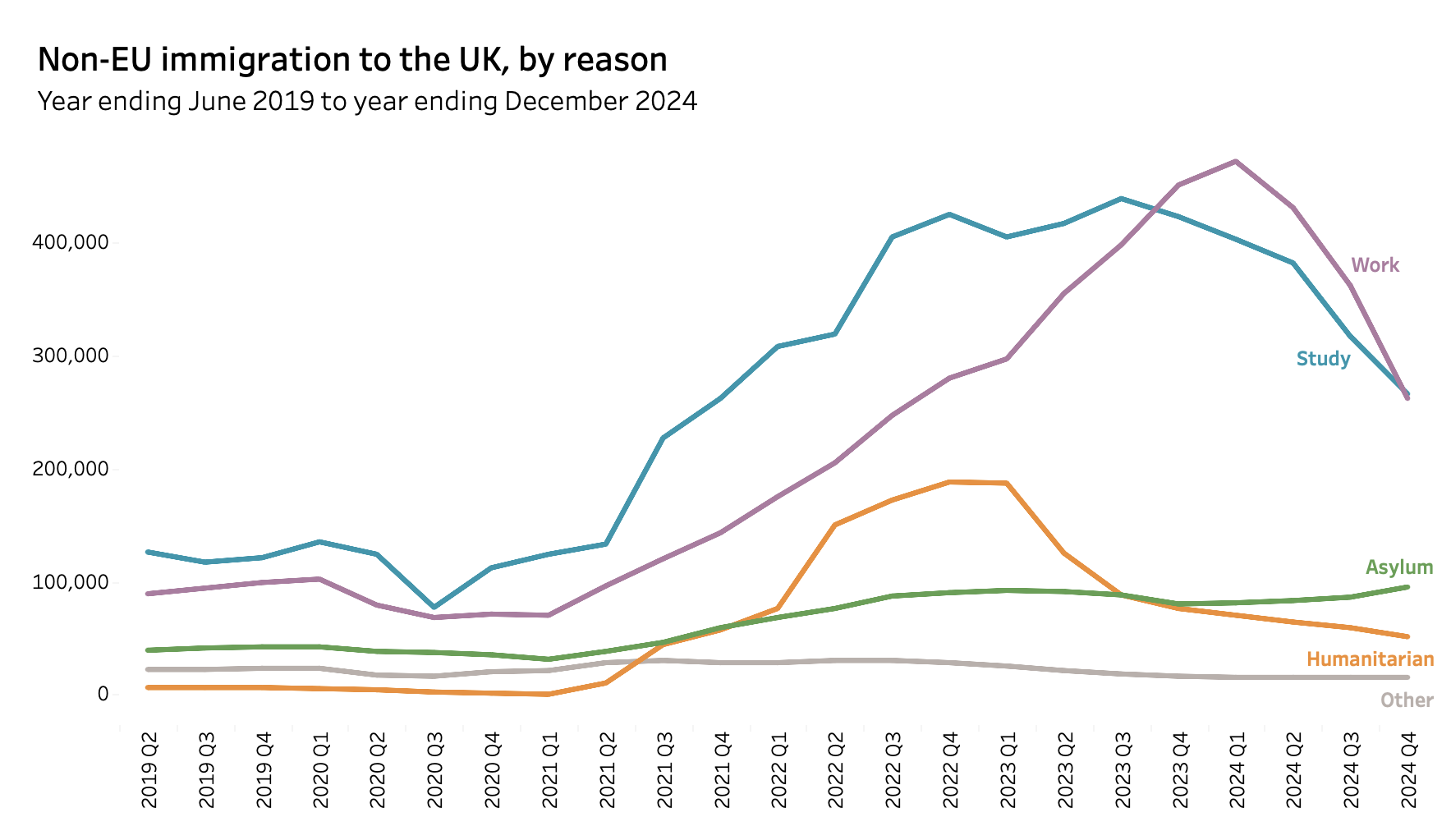

The discontent that spilled over into protests has deep demographic and fiscal roots, directly linked to the unfulfilled promises of Brexit. Despite statements about ‘regaining control of the borders,’ net migration to the UK, according to the Migration Observatory, amounted to 431,000 people in 2024, which significantly exceeds pre-Brexit figures. This greatly amplifies the sharp sense of ‘betrayal by the elites.’

Immigration to the UK from non-EU countries by reason (2019-2024). Humanitarian reasons include arrivals via special routes for Ukrainians and British Hong Kong citizens (overseas), as well as other small humanitarian routes. Source: Migration Observatory

Immigration to the UK from non-EU countries by reason (2019-2024). Humanitarian reasons include arrivals via special routes for Ukrainians and British Hong Kong citizens (overseas), as well as other small humanitarian routes. Source: Migration Observatory

This flow has taken on a radically different form: the driving force behind migration has become non-European migration (69% of which was for work and study), dominated by citizens of India, Pakistan, Nigeria and China. This demographic shift (particularly racial and religious) intensifies the discourse on the ‘crisis of national identity’ and creates additional social tension, which has become a catalyst for protest sentiments. Against this backdrop, the protest movement has taken on distinctive features, combining local discontent with widespread radicalisation.

Firstly, there is the geographical decentralisation of protests and the fiscal burden. Whereas previously decisive political protests were concentrated in London, the anti-immigration movement has spread far beyond the British capital. The centres of increasing tension were not the central districts of London, but small towns and municipalities, where the burden on social infrastructure (schools, healthcare, social housing) from the influx of migrants is most severe.

It was local protests near refugee hotels (asylum hotels) that became a platform for mobilising society, because at its peak in September 2023, more than 56,000 asylum seekers were staying in hotels. Although this number had fallen slightly by June 2025 (to 32,059), it remains critically high and has increased by 8% compared to the same period last year. Keeping migrants in hotels has become a financial burden, causing considerable outrage among taxpayers. The government spent around £8 million per day on this in September 2023. Overall, the annual cost of accommodating and supporting asylum seekers in hotels was estimated at around £3 billion. This has become one of the strongest arguments used by populist and far-right forces to boost protest movements.

Secondly, radicalisation and media coverage as a feature of this process. The movement quickly transformed from a ‘local residents' protest’ into a tool for mobilising populist and far-right forces. They use social media and other available platforms to spread openly xenophobic appeals, which contributes to a rapid transition from peaceful demonstrations with posters to clashes, aggravating the security challenge. According to KCS data, the number of cases registered as crimes involving knives or sharp objects exceeded 50,000 in the year leading up to March 2025. Although the cause-effect link between migration and crime is often subject to political manipulation, in radical circles the rise in crime is clearly associated with ‘uncontrolled’ migration.

Thirdly, illegal arrivals of migrants. The problem of illegal crossings of the English Channel in small boats is particularly acute: around 37,000 people were detected in 2024. This constant, media-covered flow, despite the authorities' promises to ‘stop the boats,’ is perceived as a complete loss of control, reinforcing the sense of betrayal among the electorate that voted for Brexit.

In the long term, the current situation could have serious consequences that could destabilise the established political order. The most critical consequence is the crisis of political centrism in the UK and the unprecedented undermining of the government's position. The Labour Party has been under fire from the right wing of the opposition for its inability to stop boats in the English Channel and for its lack of an alternative solution to migration issues after the cancelling of the Conservative government's controversial project, unofficially known as the "Rwanda Plan ", which provided for the redirection of migrants from the United Kingdom to Rwanda.

In addition to the issue of migration, where the Labour government has completely failed, there is also criticism of the slow pace of addressing social problems, in particular the housing crisis. These problems are aggravated by deep fiscal instability. Rising debt servicing costs and a persistent budget deficit are limiting the government's ability to invest in social services and housing, contributing to public discontent.

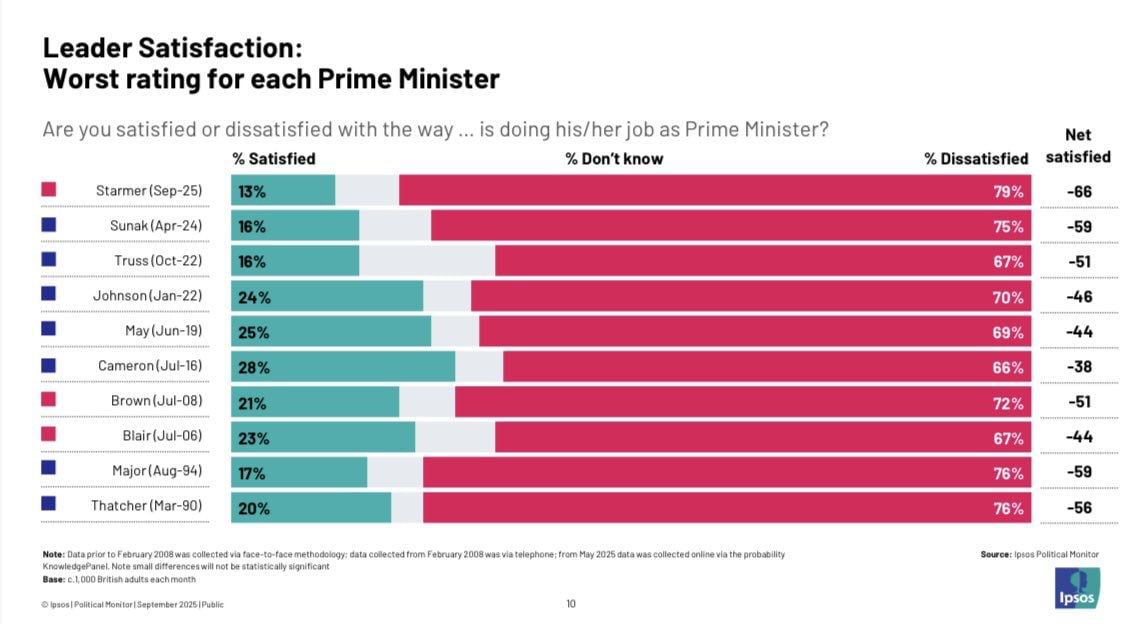

This pressure is rapidly depleting the political capital of Keir Starmer himself, who, according to IPSOS, has topped the list of government leaders with the lowest approval rating (13%) in his 15 months as Prime Minister, which is an anti-record compared to other Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom.

Anti-rating of British prime ministers. Source: IPSOS poll

Anti-rating of British prime ministers. Source: IPSOS poll

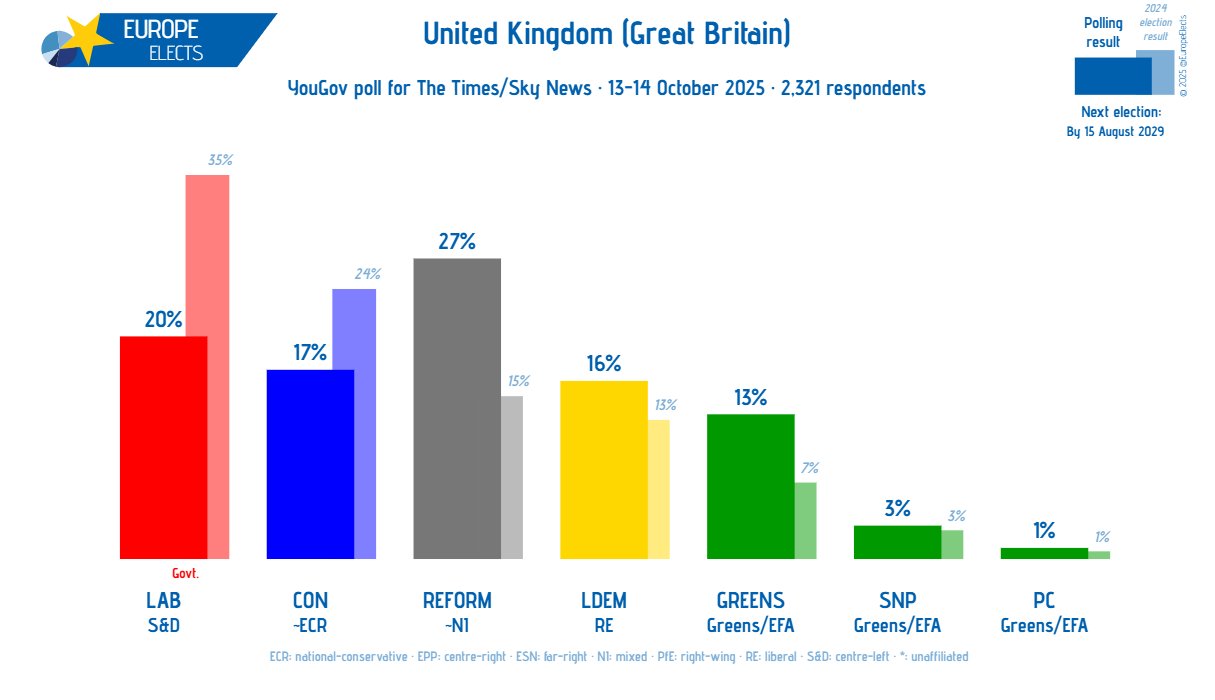

Due to the problems of the Labour Party, the popularity of far-right and populist forces (in particular Reform UK) is growing, offering simple and radical solutions and winning the sympathy of both Labour and Conservative voters. Growing fatigue with traditional forces that are unable to overcome problems plays into the hands of populist parties that are serious about solving the migration issue, which is directly reflected in the ratings. According to a YouGov poll (5-6 October), Reform UK is in the lead with a significant advantage, with 27% support. At the same time, the Labour Party received 20% and the Conservative Party only 17%. This unprecedented decline in support for traditional forces demonstrates a deep crisis of confidence.

Level of support for political forces in the United Kingdom (YouGov poll for The Times/Sky News, 5-6 October 2025). Source: Europe Elects

Level of support for political forces in the United Kingdom (YouGov poll for The Times/Sky News, 5-6 October 2025). Source: Europe Elects

In the long term, the rapid growth in support for non-systemic parties such as Reform UK carries the risk of fragmenting the British political system. Despite the stabilising influence of the majoritarian electoral system, which traditionally promotes a two-party system, such a ‘shift to the right’ and the outflow of voters from centrist forces could undermine the historical two-party model. This will inevitably increase political instability and create difficulties for the formation of a stable majority and effective governance in the future.

All this is just part of the potential major changes that could radically transform the UK, which is experiencing a ‘shift to the right’ against the backdrop of the triumph of similar forces in other countries and severe social and economic hardship, which is perceived as a humiliation of national pride.

The crisis in the UK inevitably raises questions about London's reliability as a key ally of Kyiv. Despite acute internal division, support for Ukraine remains a strategic constant, but it should be understood that internal instability could affect the quality of this support.

Support for Ukraine has a certain ‘immunity’ to internal crises and electoral volatility, which is based on three principles that are common to the entire political establishment:

1. Bilateral agreements and elite consensus. Aid to Ukraine has deep institutional roots. The Agreement on a Century-Long Partnership between London and Kyiv, signed on 16 January 2025 and officially entered into force on 15 October 2025, is particularly relevant. This document is a long-term commitment that transcends any party cycles. The amount of assistance is set at a minimum of £3 billion per year until 2030–31.

However, the question of its irreversibility remains open: detailed security commitments are set out in a separate ‘Century Partnership Declaration,’ which is not subject to ratification. Moreover, both the Agreement and the Declaration contain provisions on the possibility of unilateral termination by either Party by giving six months' written notice. Thus, although none of the leading political forces would dare to denounce the agreement, the risk of termination of military aid legally exists.

2. Global Britain as a foreign policy anchor. For London, support for Ukraine is a key element of its post-Brexit strategy. It allows the UK to strengthen its status as a global leader in security, strengthening relations with the US and NATO, and demonstrating decisiveness in the face of aggression. Withdrawing support would cause irreparable damage to international authority.

3. Strong public opinion. The British public remains strongly committed. Even against the backdrop of economic problems, more than 50% of Britons continue to support the provision of economic, humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine.

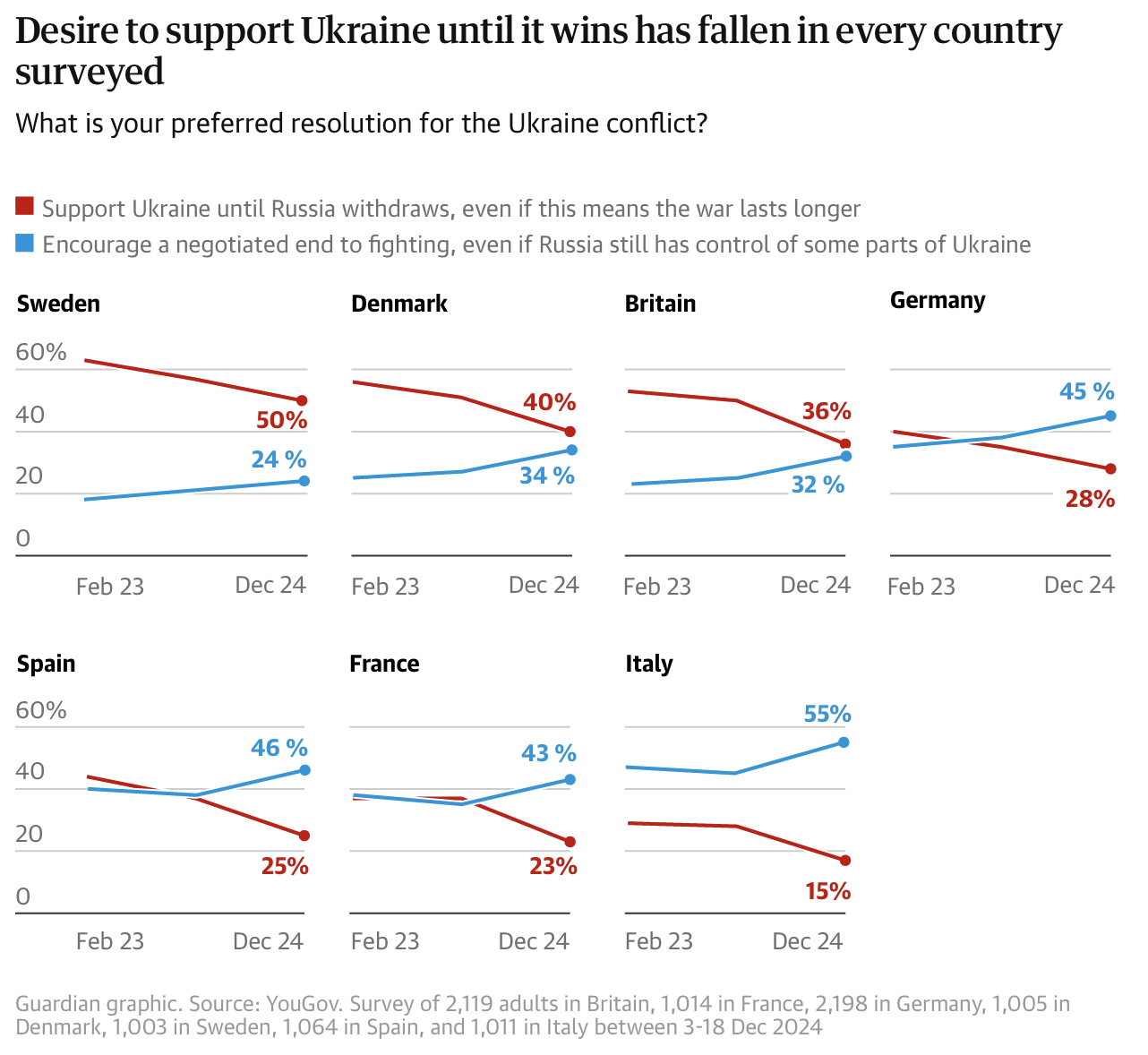

However, there is a negative trend: the proportion of those willing to support Ukraine ‘until victory and the complete withdrawal of Russian troops, even if it prolongs the war’ has fallen sharply. While at the beginning of 2024, around 50% of citizens supported this approach, by the end of the year this figure had fallen to 36%. Nevertheless, this public agreement creates a pro-Ukrainian consensus that forces even populist forces such as Reform UK to demonstrate pro-Ukrainian rhetoric in the context of political struggle, as otherwise they risk losing part of the electorate for whom the protection of Ukraine's sovereignty remains important.

Level of willingness to support Ukraine until victory in different countries (red line – support for Ukraine until victory and complete withdrawal of Russian troops, even if this prolongs the war; blue line – encouragement of negotiations to end hostilities, even if Russia still controls some parts of Ukraine). Source: YouGov poll; Guardian

Level of willingness to support Ukraine until victory in different countries (red line – support for Ukraine until victory and complete withdrawal of Russian troops, even if this prolongs the war; blue line – encouragement of negotiations to end hostilities, even if Russia still controls some parts of Ukraine). Source: YouGov poll; Guardian

However, the internal crisis will still have an impact on London's activity and ambitions on the international stage, making it a less proactive partner. Therefore, three key risks that Ukraine may face should be noted here, namely:

Dispersion of political capital and reduced activity. When the government focuses its efforts on overcoming internal problems (fiscal crisis, migration unrest and rising populism), it inevitably loses its capacity for active participation in the international arena and leadership. The UK is the driver of the ‘Coalition of the Willing’, the leader of the ‘Ramstein’ group and a key communicator with the US on Ukraine. Accordingly, focusing on domestic problems could lead to a decline in London's activity in promoting new sanctions, creating new military formats, and slowing down discussions on potential security commitments for Ukraine. Foreign policy could be dominated by the principle of ‘honouring existing commitments’ rather than actively promoting new initiatives.

Decline in international authority and weakening of ‘soft power’. Internal chaos and instability undermine the UK's international authority. Although military aid remains significant, London's ‘soft power’ as a negotiator and ‘advocate’ for Ukraine may be weakened. This could indirectly affect its ability to effectively lobby for Kyiv's interests among less determined allies.

Budgetary pressure and populist rhetoric. The social crisis, exacerbated by rising public debt (95.3% of GDP) and budget borrowing (£99.8 billion), may increase demands for the redistribution of funds to address domestic problems amid populist rhetoric. Although this demand is unlikely to be accepted due to the impossibility of reducing strategic aid, it could create political pressure and noise that would complicate the adoption of additional aid packages.

The possibility of Starmer's government resigning. Keir Starmer's ultra-low approval rating (13%) and his weak position even within the Labour Party create a real possibility of early resignation. This could happen even without a vote of no confidence, for example, after the poor results of the Labour Party in the May 2026 local elections in Scotland, Wales and London. Such an early change of leader, or even the complete collapse of the coalition, carries the risk of temporary paralysis in key decision-making, including on the issue of continued support for Ukraine. Although this would not mean an immediate change in foreign policy, uncertainty and political chaos could delay critical supplies and diplomatic efforts.

You may be interested