INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL

COMMUNITY

+ Join

Support

Kateryna Vodzinska, expert at the Resurgam think tank on Southeast Asia and China

Getty Images

Getty Images

To understand how the CPC functions, one must look at its history. The CPC has gone through several key stages in its development. From the struggle against nationalists and radical reforms under Mao Zedong to Deng Xiaoping's reforms, which changed the country while maintaining one-party control and ensuring stable economic growth. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the party learned from the experience of others and focused on strengthening its own power, preventing political liberalisation that could threaten its monopoly. In the 1990s and 2000s, a system of collective leadership emerged, with leaders changing every two terms, following the path set by Deng Xiaoping. However, in recent years, there has been a new twist: after Xi Jinping was elected General Secretary in 2012, the party returned to a more centralised, personalised style of governance. The highest position in the party is General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee, the de facto leader of the country. He also heads the most influential structures, in particular, he holds the post of Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the CPC, the body through which the party controls the People's Liberation Army of China. In essence, this is the party's supreme headquarters: the head of the CPC is also the head of the CMC, i.e. the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. There is a state military council of the same name in the PRC, but it is the party's Central Military Commission that determines military policy, guaranteeing the principle of the party's supremacy over the army. In other words, the organisational structure of the CPC ensures the concentration of power at the top of the party and the penetration of party control into all state institutions.

Xi Jinping has gradually concentrated more personal power in his hands than any other post-Mao predecessor, and has even abandoned the practice of nominating a clear successor for the future. In 2018, the two-term limit on the presidency was abolished, paving the way for Xi's de facto indefinite rule.

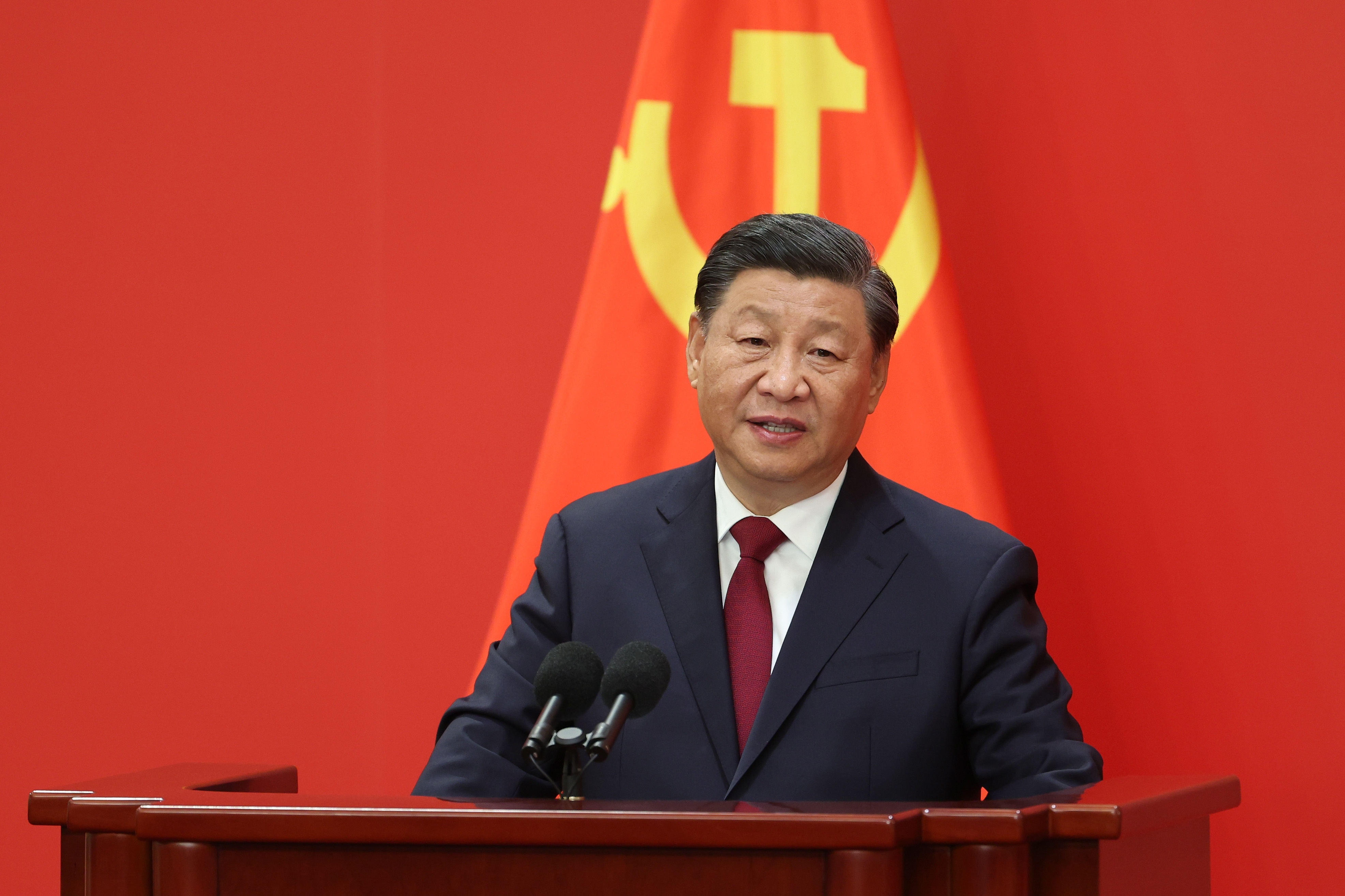

![Xi Jinping (officially re-elected)[[https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/news-63346636]] for an unprecedented third term as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China](https://assets.resurgamhub.org/f/302191/1200x800/0c54080098/1.jpg) Xi Jinping officially re-elected for an unprecedented third term as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China. Photo: Marko Djurica

Xi Jinping officially re-elected for an unprecedented third term as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China. Photo: Marko Djurica

The problems faced by the CPC are quite clear to all of us.

Corruption has traditionally posed a serious challenge to the CPC and the Chinese state, especially since the period of economic reform, when opportunities for abuse of power increased. Corruption scandals involving high-ranking officials periodically arose within the party, undermining its authority. With Xi Jinping's rise to power, an unprecedented anti-corruption campaign was launched, the largest in the history of the PRC. Xi Jinping proclaimed the slogan of fighting both ‘tigers’ and ‘flies,’ meaning the equally unforgiving prosecution of both high-ranking officials and minor officials involved in bribery. In the first years of the campaign, dozens of influential figures and thousands of lesser officials were investigated; most of them were removed from office and prosecuted for bribery or abuse of power. As of 2023, approximately 2.3 million officials at various levels have been investigated and punished – an unprecedented scale of purges that has become Xi's trademark policy. For the first time in decades, members of the top leadership have been targeted. Criminal cases were brought against several former members of the Central Committee and the Politburo. The most high-profile case was that of Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Politburo Permanent Committee (de facto one of the country's rulers) who was sentenced to life imprisonment for corruption. Former Chinese security minister sentenced to life imprisonment

Former Chinese security minister sentenced to life imprisonment

In recent years, China has faced significant economic challenges that have tested the CPC's ability to govern the country effectively. The once-incredible pace of growth has been replaced by an economic slowdown. Among the reasons are structural factors such as an ageing population and market saturation, as well as external factors such as trade wars and sanctions. The once incredible growth rates have been replaced by an economic slowdown. Among the reasons are structural factors, such as an ageing population and market saturation, as well as external factors such as trade tensions with the United States. The most serious problem has been the crisis in the real estate market. The construction boom, which lasted for many years and accounted for a significant share of GDP (about a quarter of the country's economy), led to the overheating of the sector. Thus, the once growth engine – the construction sector – has become a risk factor for China's economic stability. The photo shows unfinished residential complexes in the Chinese province of Shaanxi, illustrating the crisis in the real estate market. After the default of construction giant Evergrande in 2021, this sector went into sharp decline. According to estimates for August 2023, there are about 7.2 million unsold new apartments in the country. The CPC leaders realise that economic difficulties pose political threats too, so they are trying to intervene and correct the situation. Photo: Reuters

The photo shows unfinished residential complexes in the Chinese province of Shaanxi, illustrating the crisis in the real estate market. After the default of construction giant Evergrande in 2021, this sector went into sharp decline. According to estimates for August 2023, there are about 7.2 million unsold new apartments in the country. The CPC leaders realise that economic difficulties pose political threats too, so they are trying to intervene and correct the situation. Photo: Reuters

Constitutionally, there are several ‘democratic parties’ in the PRC, but they are not opposition parties and operate under the control of a single Front led by the Communists. All branches of government, the media, the judicial system, the army and the security apparatus are controlled by the party leaders. Under Xi Jinping's reign, this control has only intensified, the regime has become even more authoritarian and repressive, and the party strictly regulates society – from internet censorship and ideology in universities to the suppression of the slightest manifestations of dissent.

In the absence of external opposition, the main political intrigue is possible only within the CPC, and changes in the party leadership can significantly influence the country's course. For example, Xi Jinping's rise to power marked the end of the former principle of collegial governance and a transition to the concentration of power in the hands of one person. Moreover, the new Permanent Committee of the Politburo consists exclusively of Xi's close associates, with no representatives of the so-called old guard.

A few recent events in China's ruling circles have sparked speculation about whether Xi Jinping's grip on power is weakening. The Politburo of the Communist Party of China has issued unusually worded statements, and some of Xi's allies have been removed from key positions. These signals may indicate an internal struggle for influence. At the same time, their interpretation is not clear-cut – experts are divided on whether this indicates a weakening of Xi's position or, on the contrary, another stage of consolidation of power.

At the Politburo meeting on 30 June, the Chinese leaders used a number of coded phrases that attracted attention. In particular, calls were made for 'strengthening policy coordination' and 'changing the approach to key tasks'. At first glance, such formulations sound like the centre's intention to ensure the implementation of its programmes at the local level. However, the details of the statement hint at a deeper subtext. The Politburo indicated that specialised bodies under the Party's Central Committee — the same influential commissions currently headed by Xi's appointees — should focus on ‘leading and coordinating key initiatives’ and ‘avoid interfering in the responsibilities of others or exceeding their authority.’ This unusual advice looks like a warning to Xi himself, who is accused of extensive abuse of his power.

This interpretation is supported by the context, namely the lack of transparency in decision-making among the top leadership of the PRC, which traditionally forces people to read between the lines of official statements. Now, however, the party elite seems to be sending signals about the need to restrain the concentration of power in one person. In other words, the very mechanism of collective leadership of the Communist Party may be trying to limit the omnipotence of a single leader.

It can be said that today Xi Jinping's power appears monolithic and externally unshakeable. However, this stability is more of a strong shell than a guarantee of sustainability. The medium-term outlook is much more complex: it will be determined by the leaders’ ability to overcome accumulated economic and social problems. If the Chinese economy does not return to steady growth, this will significantly slow down the country's course towards global hegemony, and internal party problems will begin to escalate into major scandals, which in turn poses a great reputational risk to the regime. A system where all important decisions are made behind closed doors creates fertile ground for internal party conspiracies and the redistribution of influence. To maintain control, the leader will need to combine harsh, repressive methods with real steps to solve the economic and social problems that concern both the people and the elite.

The coming years will be a test of the regime's flexibility. Will Beijing be able to find new points of economic growth, reduce social tensions and avoid management mistakes that could undermine Xi's authority from the inside? To keep the country on a path of stability and development, Xi will have to balance between firmness and adaptability, between control and flexibility. This balance is crucial. It will determine China's future in the upcoming decade.

Against the backdrop of the slowdown in the Chinese economy and tight control over the elites, the question arises whether Xi Jinping could deliberately provoke a military crisis around Taiwan to consolidate internal support.

On the one hand, it is clear that Beijing feels that the window of opportunity is closing, and Xi himself has ordered the People's Liberation Army to be ready for a forceful scenario regarding Taiwan by 2027. In this interpretation, the lack of time pushes the leader of the PRC towards the option of ‘unification’ by force before Beijing loses favourable conditions. On the other hand, historically, the CPC has not used ‘distracting wars’ to resolve internal issues. China's current economic problems, although serious, are not yet dramatic enough to force the regime to take the risk of a total war. Instead, Xi Jinping is likely seeking to stabilise the economy and strengthen the army, laying the groundwork for future confrontation, but without direct conflict right now.

The strategic risk of a direct attack on Taiwan remains extremely high. A full-scale invasion would almost certainly cause a global economic shock, from the disruption of critical sea routes to a devastating blow to the global semiconductor industry. A military conflict with Taiwan would inevitably involve the United States and its allies, threatening a direct confrontation between nuclear states. Beijing realises that a situation in Asia similar to Russia's war against Ukraine would lead to devastating Western sanctions, which the Chinese economy is not ready for at the moment. Experts say that China has not yet gained the decisive military advantage required for a successful amphibious opera Despite the rapid modernisation of the PLA, there are still gaps in readiness: insufficient amphibious aviation and maritime transport to transfer troops across the channel, limited capabilities for rapid repair of runways, problems with the integration of the submarine fleet, and lagging combat training of the air force. Corruption and organisational shortcomings in the PRC's army and defence industry also play a role, undermining combat readiness despite the official completion date for modernisation. Therefore, even with maximum mobilisation of forces, Beijing risks to fail the operation now– and this would mean not consolidation, but, on the contrary, the collapse of the regime's legitimacy. A Chinese J-15 fighter jet takes off from the "Shandong" aircraft carrier during exercises around Taiwan (April 2023)

A Chinese J-15 fighter jet takes off from the "Shandong" aircraft carrier during exercises around Taiwan (April 2023)

In the next few years, Xi Jinping will likely continue his policy of ‘pressure without war’: maximising military presence around Taiwan, testing the reaction of the US and the island's authorities, but avoiding direct invasion. Beijing will seek to force Taipei to surrender without a fight – through exhaustion (the “boa strategy” - a tactic, where constant tension is supposed to force Taiwan to capitulate). If this calculation does not work, and the internal and external dynamics for the PRC deteriorate, for example, the strengthening of pro-independence sentiments in Taiwan or the expansion of military aid to the island from the West, the risk of a forceful option at the end of the 2020s will increase. The turning point is 2027, the time of the next 21st Congress of the Communist Party of China, at which Xi may seek an unprecedented fourth term. By that time, he clearly wants to have achieved clear success in the Taiwan issue or at least to have prepared the country as much as possible for a potential conflict.

The strengthening of the authoritarian Beijing-Moscow tandem is becoming increasingly apparent in the geopolitical sphere. China has effectively invested in Putin's regime, providing Russia with economic support in its war against Ukraine. Over the three years of the war, Beijing has increased its purchases of Russian energy resources and supplies of critical goods — from microchips to machine tools — helping the Kremlin withstand sanctions pressure. China's share of Russia's foreign trade has grown to a third, making Moscow economically dependent on the Middle Kingdom. Politically, Xi Jinping has repeatedly demonstrated his support for Putin, and Chinese-Russian military exercises have also become more frequent and complex, including the coordination of air strikes and command centres of the two armies. For Ukraine, this axis of autocracies means that Russia will not find itself in complete isolation — Putin has a powerful partner interested in ensuring that the Kremlin does not lose. The PRC is not directly involved in the conflict, but its ‘neutrality’ is in fact beneficial to the aggressor, as the long war is exhausting the West and diverting resources from the US and Europe. Beijing is not seeking a quick peace on terms that would weaken Moscow, as the continuation of the war plays into its hands – it ties the hands of the West in Europe and strengthens Russia's dependence on China.

Also, Xi's concentration of power makes China's foreign policy more predictable and pro-Russian from Ukraine's point of view. Whereas there were previously hidden debates in China between pro-market elites and party ideologues regarding the feasibility of rapprochement with Russia, any internal opposition to Xi's approach has now virtually been eliminated. The Chinese leadership is consolidated around its leader. Instead, a strategy of confrontation with the US prevails, with Russia seen as a necessary partner in an anti-Western coalition. For Ukraine, this means that hopes of diverting Beijing from supporting Moscow are minimal. At the same time, Beijing has set ‘red lines’ for the Kremlin: The Chinese leadership has made it clear that it opposes the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine and the Kremlin's fuelling of additional conflicts in Central Asia. However, these restrictions are sufficient for China to continue supporting Russia, enabling it to continue fighting without taking steps that could harm Beijing's own interests.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping during a meeting in Beijing (October 2023)

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping during a meeting in Beijing (October 2023)

Therefore, from Ukraine's point of view, the risks are doubled: Moscow gains more strategic opportunities if the West is distracted, and Beijing gains additional leverage over the Euro-Atlantic community, hinting that ‘there are more important priorities than Ukraine.’

Ukraine needs to act proactively, namely by strengthening alliances, seeking new support outside the traditional West, and preparing for possible shock on the international stage. The Ukrainian people have already demonstrated that they are capable of standing up to a formidable enemy. Now it is important to ensure that global support does not weaken, even in turbulent times when the future of not only Ukraine but also the fundamental principles of the international order is at stake. Maintaining the stability and unity of the democratic world will be the best guarantee of Ukraine's security in the face of new challenges.

You may be interested