INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL

COMMUNITY

+ Join

Support

Matviy Sukhachov, commentator on British politics, exclusively for Resurgam

During the Russian-Ukrainian war, sanctions became one of the main means of pressure on Russia, with a very broad punishing effect. They are aimed at the economy, finances and trade of the aggressor state and limit Russia's military capabilities.

During the Russian-Ukrainian war, sanctions became one of the main means of pressure on Russia, with a very broad punishing effect. They are aimed at the economy, finances and trade of the aggressor state and limit Russia's military capabilities.

The United Kingdom is one of the countries most actively imposing sanctions against Russia. However, during the full-scale invasion, London's sanctions policy was not perfect and at times showed signs of indecision or a lack of political will, which may indicate that this country has not yet fully exploited its sanctions potential against Moscow.

What is the UK's sanctions policy? What sanctions could London still impose on Russia? And what is preventing the United Kingdom from fully leveraging its sanction potential against Russia? We will answer these and other questions in this article.

Before understanding how the United Kingdom can further harm Russia, it is necessary to determine what sanctions London has already imposed on the aggressor state since the start of the full-scale invasion, and which of them have had the greatest effect on the enemy.

One of the largest packages of sanctions was imposed on the day of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine – 24 February 2022. At that time, the British government, in cooperation with its Western partners, announced an ‘unprecedented’ package of sanctions, which included the following restrictions:

A ban on key Russian industries and companies raising funds on British markets;

A suspension of several Russian banks' access to the UK payments system (including Russia's second-largest bank, VTB/Vneshtorgbank);

A ban on travel to the UK and the freezing of assets of many oligarchs and individuals close to Putin's inner circle;

Banking restrictions for Russian citizens;

A ban on Aeroflot flights into British airspace, etc.

By taking this step, the UK clearly sided with Ukraine and opposed Russia's aggression.

However, this ‘unprecedented’ package of sanctions was more tactical than strategic in nature. Against the backdrop of ongoing hostilities and the failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive in 2023, London had to move on to the constant and regular development of sanctions packages and closer cooperation with the G7, the EU and the US. At the same time, the main targets of the sanctions were Russian financial institutions, strategic sectors of the Russian economy, large state-owned companies and representatives of the country's political and military elite.

Exactly one year after the start of the full-scale war, on 24 February 2023, the United Kingdom announced a new serious package of sanctions. First, it included a ban on the export of all goods that Russia uses on the battlefield: aviation parts, radio equipment, components for the production of UAVs, etc. This move was intended to undermine Russia's military capabilities on the battlefield, but the Russians were able to overcome these restrictions thanks to support from North Korea, Iran and China.

It is also worth noting that the sanctions targeted important figures as top-managers from Rosatom and, CEO of Nord Stream 2 - Matthias Warnig, who is a close friend of Putin.

On 6 December 2023, sanctions were also announced against individuals and groups involved in financing Russia's military machine, most of which were companies and organisations from foreign countries – Belarus, Uzbekistan, China, the UAE, Turkey and Serbia.

The most extensive and powerful sanctions were announced and then implemented by the British government on 23 February 2025 and 9 May of the same year. The first package included 107 sanctions, which also targeted Russia's energy revenues – primarily 40 vessels of the so-called "shadow fleet" that transport Russian oil (in this case, these vessels transported oil worth more than $5 billion in six months).

The second package also contains sanctions, most of which were directed against the Russian "shadow fleet". However, they are more severe and broader in scope, imposing restrictions on approximately 100 oil tankers that have transported cargo worth more than $24 billion since the beginning of 2024. In this case, Britain has taken the lead among European countries by striking a significant blow against Russia's shadow fleet.

London's recent intensification of sanctions against Russia can be explained not only by the British government's steadfast position in support of Ukraine, but also by Trump's coming to power in the US, which has greatly reduced Washington's role in imposing sanctions against Russia.

Firstly, the UK pursues its sanctions policy independently from the rest of Europe, as it left the European Union in 2020. As a result, Britain has its own legal basis for its sanctions policy, which was formed on the basis of the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act (SAMLA), adopted in 2018.

This law allows the government to develop, implement and administer sanctions aimed at fulfilling the obligations of the UN Security Council, preventing terrorism in Britain, promoting national security interests, respecting the rights and freedoms of the country's citizens, promoting the resolution of armed conflicts, etc. In other words, this law includes a number of grounds on which the British government can impose sanctions against an aggressor country.

The advantage of this law is that, unlike the EU's sanctions policy, the British version sets out in more detail the criteria for including individuals and legal entities on the sanctions list. This, in turn, leads to higher standards of proof, which is an important part of a transparent and fair legal process.

On the other hand, detailed standards of proof slow down and bureaucratise the imposition of sanctions against individuals or countries that violate human rights, as the government is often forced to prove the need for sanctions in order to avoid being suspected of arbitrariness.

In the case of Britain, it was the legislative framework that formed the basis for all other strengths of the country's sanctions policy, the main one being the widespread use of various methods of pressure that weaken the economic and, as a result, military capabilities of the aggressor country. These methods of pressure included ‘blocking sanctions’ (freezing assets, prohibiting transactions with individuals or legal entities), export controls, sectoral restrictions, restrictions on the freedom of movement of various individuals, etc. Over time, the various sectors of the Russian economy that fell under this list only expanded (such as the introduction of sanctions against the Russian Federation's shadow fleet, which was a source of oil revenues for the country).

Returning to the analysis of the SAMLA law, another important and positive aspect for Britain is judicial restraint, which also strongly distinguishes it from EU member states. In Europe, the legal vulnerability of sanctions remains quite common, where a person subject to them can file a lawsuit to lift the restrictions. In Britain, there are fewer problems with this, because, firstly, these sanctions are repeatedly reviewed by judges and, secondly, based on this ‘detailed evidence’ procedure, it is more difficult for the accused to ‘get out’ of court cases and have the sanctions lifted.

An example of appeals to lift sanctions being rejected by judges is the incident involving Yevgeny Shvidler, a person close to Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, when the court rejected the billionaire's attempt to have the sanctions against him declared illegal.

Despite this, Britain's sanctions policy has the following weaknesses:

Insufficient scaling of sanctions packages, unlike the EU or the US, and therefore UK often turns to cooperation with them;

Rather strong dependence of the executive bodies that impose sanctions (such as the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation – OFSI) on the decisions of the government and parliament;

Russia's ability to evade sanctions through third parties (China, Iran, North Korea), which also requires the UK to spend its resources and time;

The fragmentation of the sanctions policy and the lack of a strategic vision that would allow sanctions to be imposed in those areas of the Russian economy that have long remained untouched.

Political processes that influence the political will and motivation of the British government to impose sanctions play a separate role.

To answer this question, we need to look again at areas where the British have already imposed many sanctions but have overlooked ‘grey schemes’ or even some obvious things that Russia can still use to finance its bloody war.

Let's start with energy resources – the main ‘pillar’ of the Russian economy. Officially, starting in 2022, the UK banned oil imports. However, the sanctions imposed on the purchase and transport of oil did not apply to other routes used by Russia, as well as third countries and those individuals in the UK who benefit from doing business with Moscow.

Back in 2024, news emerged that the UK had imported 5.2 million barrels of petroleum products refined from Russian oil in countries such as India. Such imports are not illegal, as these refined products are no longer considered Russian, but these purchases greatly undermined the sanctions imposed by Britain against Russia.

When talking about minerals, we should also mention resources that the UK didn't put big sanctions on for a long time and kept importing, like steel, aluminium, copper, and so on. It was only in April 2024 that London, together with Washington, banned imports of aluminium, copper and nickel, which also affected Russia's revenues.

Another tool that Britain can use against Russian energy resources is price restrictions, i.e. setting a price limit that Russian exporters cannot exceed. This makes Russian energy resources cheaper, which also reduces Russian revenues.

One more important source of income for the Russian economy is finance and banking systems. Likewise, the British have applied their sanctions in a rather selective and fragmented manner, bypassing various Russian individuals and legal entities or not applying the full force of the sanctions.

An example of this is Russian assets, most of which Britain froze a long time ago and plans to use the profits from. It is known that London plans to allocate funds from frozen assets to armaments and equipment repairs for Ukraine in the amount of about $3 billion during 2025-2026.

Here it is important to distinguish between the concepts of ‘freezing’ assets and ‘confiscating’ them, since in the case of confiscation, frozen assets are legally transferred to another party, fully. However, the UK has not had much success with this so far, and the only known case of confiscation of frozen Russian assets involves Russian oligarch Petr Aven, who in July 2024 agreed to the confiscation of more than £750,000 to end a two-year investigation by the police and the National Crime Agency (NCA).

Another example related to the financial sector is SWIFT and Russian banks' access to this international interbank system. Back in 2022, at the start of the full-scale war, many different Russian banks (VTB, Sovcombank, Promsvyazbank) were banned and left without access to international payments from SWIFT. However, Britain did not impose all these sanctions on its own, but together with the United States and the European Union. But Britain itself still cannot single-handedly deprive other banks of access to SWIFT. Minor restrictions also applied to such giants of the Russian banking sector as Sberbank and Gazprombank, which continue to actively work for the benefit of the Russian economy.

It should also be remembered that the sanctions, which may have affected individual and ‘visible’ banking companies, may have bypassed small but numerous Russian banks through which the Kremlin's military machine continues to receive money. Therefore, London also has work to do in this area.

Plus, we must not forget about the alternatives to international systems that Russia is creating, such as the FMTS (Financial Message Transfer System), which was not affected by British sanctions at all. Although this replacement for SWIFT does not work as well or as efficiently, it still allows Russians to earn money, and the FMTS itself is already operating in other countries.

What all these points have in common is that although British sanctions have affected all the financial and economic areas from which Russia can earn money, these sanctions are often selective (targeting individuals, companies, institutions, etc.), fragmented, somewhat impulsive and not as extensive as European sanctions. Therefore, the main question here is not in which areas Britain has not used sanctions, but how it should implement them — systematically, strategically, broadly, targeting entire sectors, and in conjunction with American and European efforts, while developing cooperation between parliamentary committees and increasing the powers of those bodies that implement sanctions in practice.

In addition, in order to better understand where else Russia could be inflicted with painful economic losses, the most convenient option for the British would be to focus on two things: a systematic and broad attacks on entire sectors (including shadow channels of income) and pressure on third parties through which the Russians circumvent these sanctions (for instance, China, Turkey).

Another important question is whether British politicians will have the necessary motivation and will for the adoption of sanctions. After all, politics is primarily about the interests of the players, as well as the conditions that can influence decision-making.

Theoretically, Britain has every opportunity to impose sanctions that it has not yet used against the Russian economy, as such decisions are quickly adopted in its parliament (where it is only necessary to get a majority of votes), and there is a two-party consensus on this. The SAMLA law also allows Britain to take more decisive action, giving the government and parliament all the necessary powers to impose sanctions, and the state itself, independent in its decisions, easily cooperates with Europe in terms of inflicting an economic strike on Moscow.

In practice, however, there are pitfalls such as the fear of a recession in the event of a full resource embargo by Russia, legal restrictions, the potential influence of business lobbies, and political processes.

While the first two points are more understandable, the other two points need to be analysed in more detail. In the first case, various business lobbyists working consciously or unconsciously for Russia and British companies that continue to do business with Russia and have long paid taxes to the Russian budget are against the imposition of sanctions. An example is the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, which, despite its promises, has not left the Russian market, and as of 2024, the company has paid $45 million to Russian doctors and healthcare organisations.

In the second case, Russian sanctions were opposed by various political figures who seriously feared that in the event of tougher methods of pressure, Russia would not stop the war, but rather escalate it and take asymmetric actions against the UK. However, unlike the Europeans and Americans, such sentiments were not widespread among British politicians and were more pronounced at the beginning of the war than now, when Britain is in full solidarity with Ukraine and is carefully considering new sanctions against Russia. Therefore, political fear of escalation is not as influential as lobbying or business interests.

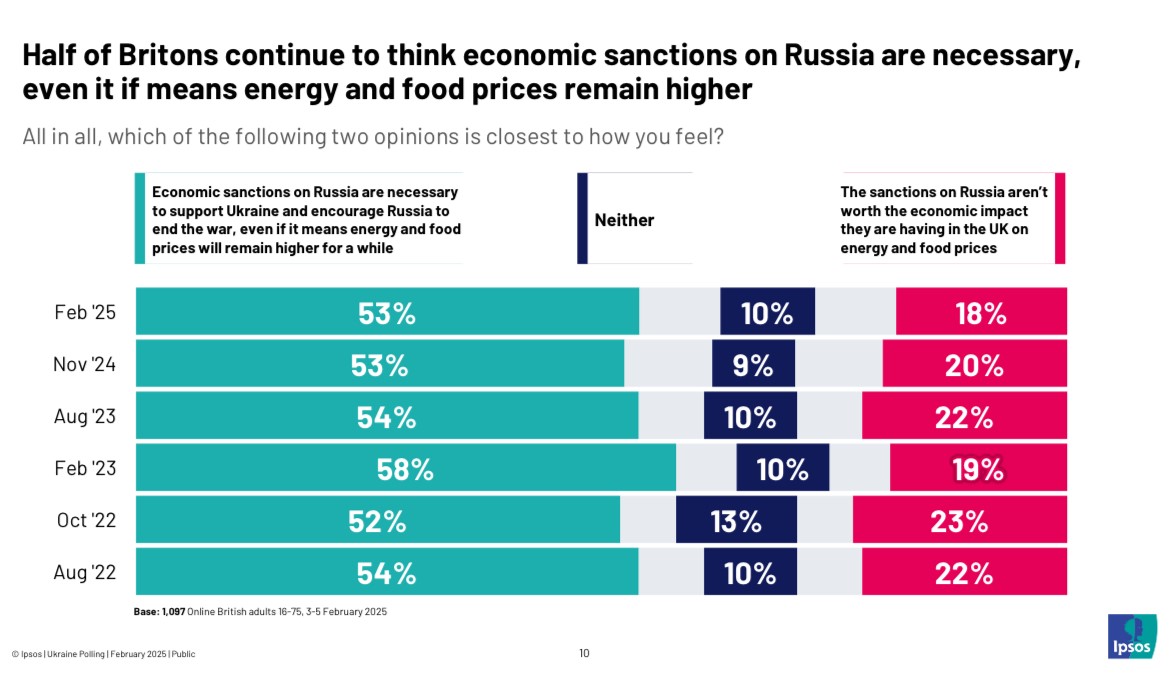

In the case of sanctions, it is important to understand public sentiment, which politicians often rely on, which is a clear sign of democracy. According to an Ipsos poll published on 23 February 2025, more than half of Britons (53%) continue to believe that economic sanctions against Russia are necessary, even if it means that energy and food prices will remain higher. Around one in five (18%) believe that sanctions are not worth the economic consequences. This figure has remained relatively stable since the beginning of the war. Results of the Ipsos poll

Results of the Ipsos poll

You may be interested