Agreement with MERCOSUR: electoral motives versus pan-European interests

Yulian Bardas, political scientist, intern at the Resurgam Center for European Affairs

Photo: Reuters

Photo: Reuters

General context

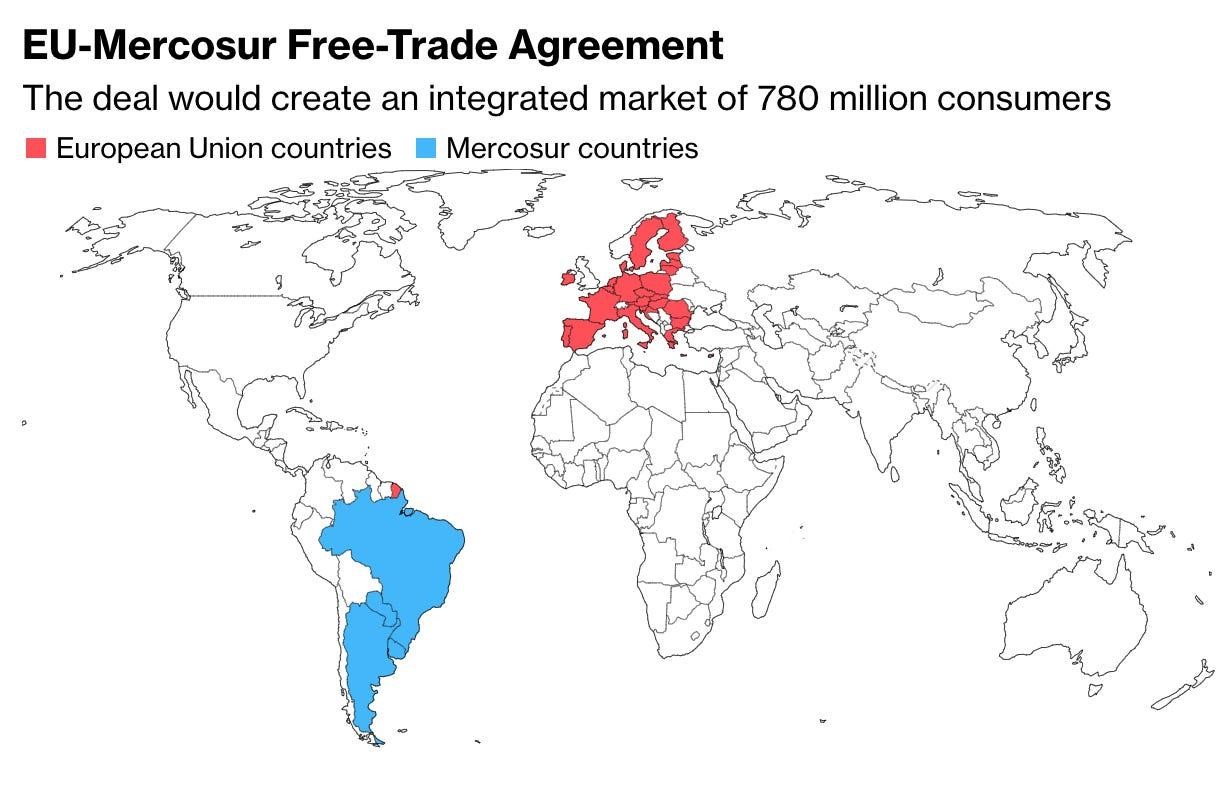

The negotiation of the agreement began in 1999, and since then it has been amended several times. It was only in 2019 that the parties reached a consensus on signing it. However, this period coincided with a change of power in Brazil: in January 2023, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva returned to the presidency, replacing Jair Bolsonaro. Former President Bolsonaro sought to develop the key agricultural sector at the expense of deforestation in the Amazon, whilst the EU announced the launch of a green course — a large-scale strategy to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, which makes environmental standards a prerequisite for international trade.

The agreement only returned to active discussion at the end of 2024. The key factor was Donald Trump, who began to pursue a policy of tariff pressure. He forced the EU to conclude unfavourable trade agreements: for example, under the framework agreement on trade and investment parameters of 27–28 July 2025, the EU must invest 600 billion in the US and purchase 750 billion worth of fossil fuels.

Trump also increased economic pressure on Latin American countries, particularly Brazil. MERCOSUR countries have no agreements or long-term guarantees for ‘safe’ trade with the US. They were partially subject to tariffs under Trump's policy. For example, during a diplomatic conflict with Brazil in June-October 2025, the US imposed a 50% tariff on products from that country. As a result, Trump's policy actually accelerated both sides' return to the concept of a trade agreement between the two blocs.

The trade agreement with MERCOSUR could be considered an unconditional victory for the European Commission, as it is direct proof of Brussels' ability to conclude large-scale geopolitical agreements. For Ursula von der Leyen, this would mean a significant increase in political weight on the world stage and would add to her authority in the global confrontation with Donald Trump and Xi Jinping. However, because the agreement never came into force after its historic signing, this triumph turned into an internal defeat, highlighting the deep crisis of decision-making within the EU itself.

The European Parliament voted by a narrow majority in favour of a resolution requiring the agreement to be reviewed by the EU Court of Justice before ratification: 334 votes in favour, 324 against and 11 abstentions. This is a classic tool of political delay — using a legal procedure (Article 218 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union) as a political brake. According to procedural rules and the average duration of cases in the EU Court (which, according to the Court's annual reports, is about 16-20 months), the final decision may be postponed for two years. This is temporary protection for farmers who are also waiting for long-term guarantees.

The main countries opposing the agreement are France, Poland, Ireland, Austria, Hungary and Spain. They are the most concerned about the state of their own agricultural sectors.

What is the agreement most criticised for?

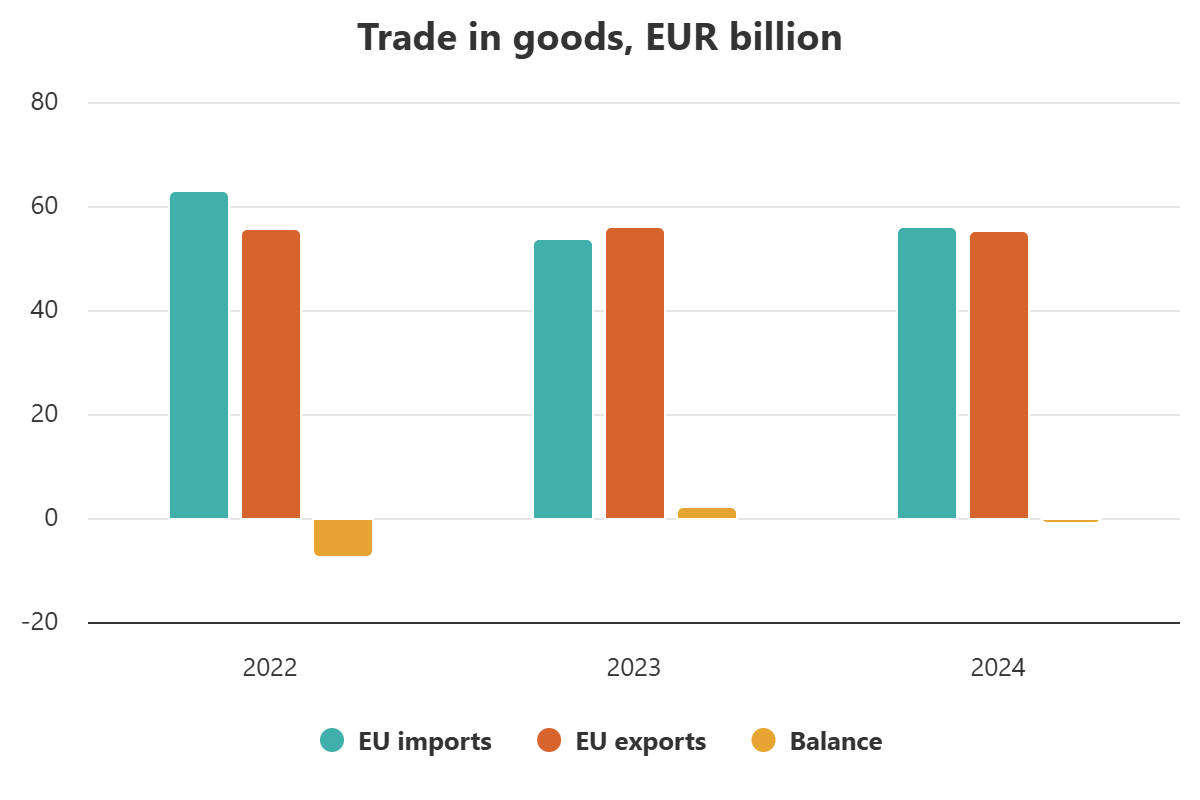

One of the key obstacles is related to agricultural products. As of today, trade between the EU and MERCOSUR exceeds €110 billion. It is almost equal in terms of exports and imports for both blocs, with a slight positive balance for the latter. At the same time, there is a significant difference in the structure of trade.

Source: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/mercosur_en

Source: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/mercosur_en

It is this difference that determines the main lobbyists for the agreement within the EU. In Germany, for example, the automotive and industrial lobby actively supported the signing of the agreement, as it provides large companies with an opportunity to enter a market previously protected by tariffs, redirect some of their exports from China and the US to Latin America, and reduce political risks.

Below are statistics on trade volumes. The EU is MERCOSUR's second largest trading partner after China and ahead of the United States. The EU accounted for 16.8% of MERCOSUR's total trade in 2024. For the EU, MERCOSUR is the tenth largest trading partner.

Of the €110 billion in trade between the EU and MERCOSUR countries, EU exports to the four countries in the region account for €53.3 billion, while imports from these countries amount to €57 billion. This results in a slight surplus in favour of MERCOSUR.

MERCOSUR's largest export items to the EU in 2024 were agricultural products (42.7% of total exports), mineral products (30.5%) and pulp and paper products (6.8%).

EU exports to MERCOSUR in 2024 included machinery and equipment (28.1% of total exports), chemical and pharmaceutical products (25%), and transport equipment (12.1%).

![Source: (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250620-3) [[https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250620-3]]](https://assets.resurgamhub.org/f/302191/1921x1080/101b29e65f/gg3.jpg)

For farmers, especially small farms, the situation is different. The influx of cheap agricultural products poses a threat: it could make the local agricultural sector uncompetitive, given its dependence on subsidies. The total budget of the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for 2021-2027 was €386.6 billion, with subsidies aimed at supporting high quality standards, environmental norms and social guarantees. This automatically leads to higher prices for European products. In Latin American countries, lower prices are achieved through cheaper labour, weaker environmental standards and lower labour standards.

It is these aspects that critics focus on, raising the key issue of protecting farmers. Initially, the EU planned to reduce subsidies to the agricultural sector in the 2028-2034 budget period. However, in order to reduce social tensions, the European Commission proposed early access to €45 billion from the CAP budget planned for 2028-2034. In addition, the CAP reserve fund was increased from €450 million to €6.3 billion.The agreement also includes provisions allowing for the emergency suspension of tariff quotas on imported goods in the event of a sharp increase in imports or a fall in prices.

The EU's internal political dilemma

The key question is whether consensus within the EU on this agreement is possible, or it will become another manifestation of the Union's structural problems.

An economically rational decision for the EU as a whole is proving to be ‘politically toxic’ for individual states. The European Commission was able to reach an important agreement because it concerns a market of 770 million consumers and about 25% of global GDP, making the agreement one of the largest economic zones in the world. At the same time, the Commission was guided by geo-economic logic, while national governments are forced to think in electoral terms.

In France, ratification of the agreement could undermine confidence in the government and lead to early elections, while in Spain, large-scale protests have taken place across the country. As a result, a confrontation is forming in the EU between two approaches to the trade agreement. For France, protecting farmers is a guarantee of political stability, while for Germany, new export markets remain critical as the basis for its strategic economic position.

As a political actor, the European Commission is trying to think long-term and resolve external and internal conflicts through compromise. In relations with MERCOSUR, they envisage the phased implementation of the agreement, gradual market access, environmental standards and investment. Within the EU, the focus has been on protective quotas and financial compensation.

However, this approach has its limits. Not all groups can be satisfied with financial instruments such as protective quotas and the expansion of the reserve fund for compensation. France, Poland, Austria and Ireland have a strong farming electorate, and any threat to the agricultural sector automatically turns into a political crisis. A compromise in such a situation is difficult to explain to voters. No trade agreement is worth the risk of losing power.

The European Parliament, as a separate political actor in the EU, is responsible for internal political signals. Referring the trade agreement to the EU Court of Justice, initiated primarily by France and supported by an unexpected coalition of right-wing groups and ‘greens’, is a way of avoiding responsibility for a decision that is already causing socio-political tensions. As we wrote above, they managed to win this political game with a slight majority of votes: 334 votes in favour, 324 against and 11 abstentions.

This creates risks for EU unity and strengthens the arguments of Eurosceptics who use the situation to criticise the bureaucratic system. In this political game, even if a compromise is reached, someone will inevitably lose. Either the European Commission will show weakness and back down, or national interests will yield to geopolitical goals.

The question remains open as to whether the EU will be able to reform structurally or whether it will remain a union of national electoral fears.

Meaning for Ukraine

This agreement creates fundamentally new risks for the Ukrainian agricultural sector. If fully implemented, Ukraine will enter into direct competition with Brazil and Argentina, global leaders whose production volumes significantly exceed those of Ukraine. For example, Ukraine's corn harvest is almost 30 million tonnes, while the combined production of MERCOSUR countries reaches approximately 180 million tonnes, creating a huge gap in supply on the European market. In addition to scale, the issue of security reliability comes to the fore. European importers may prefer contracts with MERCOSUR partners, where the risks of infrastructure destruction or logistical blockages (such as port shelling or border strikes) are minimal compared to the military realities of Ukraine.

In the context of Ukraine's European integration, the agricultural issue is already a matter of debate. Some countries, notably Poland, openly fear Ukraine's accession, seeing it as a threat to the stability of their own farming industry. This problem will become significantly more complicated if the agreement is adopted in the future. Ukraine thus risks finding itself in a situation where the European market is not only protected, but also oversaturated and exhausted by conflicts over imports.

However, the current pause caused by the court proceedings gives Ukraine the necessary time to prepare and adapt to the new market realities. This is a window of opportunity that Ukraine must use to simultaneously negotiate favourable agricultural quotas, which will protect Ukrainian interests even before the European market is finally opened.

Yulian Bardas, political scientist, intern at the Resurgam Center for European Affairs

You may be interested