INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL

COMMUNITY

+ Join

Support

Kostiantyn Hlushko, staff analyst and reviewer at the "Resurgam" Center for Northern European Policy

Photo: Bloomberg

Photo: Bloomberg

Since 2015, Sweden has resumed the implementation and continued reconstruction of a total defence system that combines military and civil security components. Total defence involves the engagement of all citizens in the defence of the country and constant preparation for war. It is a social contract between all citizens, according to which defence is a common cause.

For Ukraine, which is already at war, building a high-quality security system is a guarantee of survival. Therefore, Sweden's experience may prove to be a valuable source for its development.

What is the history of total defence in Sweden? How is the country bringing it back to life? And what should Ukraine learn from Sweden's experience? We answer these and other questions in this article.

Although Sweden did not participate directly in the world wars, even during the First World War, it became clear to the country that neutrality alone was not enough to ensure peace and security. At that time, for example, unrestricted submarine warfare led to shortages of coal, oil and food in Sweden. The shortage of bread and potatoes in 1917 was so severe that the parliamentary elections held that year were called the ‘hunger elections’ (Swedish: Hungervalet).

As a result, in 1917, Sweden established the War Preparedness Commission (Swedish: Krigsberedskapskommissionen), a body responsible for assessing and improving national defence and crisis preparedness. In 1928 (during the premiership of Arvid Lindman of the Right Party), it was transformed into the Kingdom's Commission for Economic Defence Preparedness (Swedish: Rikskommissionen för ekonomisk försvarsberedskap), which was responsible for creating reserve stocks of strategic raw materials.

At the same time, the Second World War changed the understanding of war in Sweden. In her work ‘The Military-Strategic Rationality of Hybrid Warfare: Daily Total Defence in the Absence of Peace in the Case of Sweden,’ Dr. Kristin Ljungquist writes: "Second World War changed the general perception of war because of the way it indiscriminately affected the whole society and also because the enemy population and its will to resist and fight became targets of war. The idea that total war would be waged not only against the armed forces but also directly against the people gained a foothold in Sweden..."

The first comprehensive doctrine of total defence appeared in 1942 (government of national unity, Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson). But the concept began to be implemented directly in the post-war period.

At that time, it consisted of four components: military defence, civil defence, economic defence and psychological defence.

Military defence, of course, involved protecting Sweden's territory with the help of the armed forces – using the regular army, air force, navy, and coastal artillery (which was mostly outdated in the early 1930s, but after modernisation, some guns could attack the enemy at a distance of 20 kilometres).

However, military defence is not that simple. Since at least 1911, the development of the armed forces in Sweden had been highly politicised. In 1911-1926 (with a break for World War I), there was a rivalry between King Gustav V, who insisted on the need to strengthen the armed forces, and various liberal and social democratic governments, which sought to reduce defence spending in favour of social programmes.

For example, in 1911, Liberal Prime Minister Carl Staaf cancelled the previous government's decision to allocate funds for the purchase of new battleships. In response, the king began to rally right-wing military personnel, scientists and politicians around him, with whom he created the “Association for the Battleship” in 1912, which collected donations for the construction of a modern battleship, and in 1912-1913 conducted an awareness campaign through newspapers, lectures, and public events. As a result, the full amount was raised in 1914. This led to the resignation of Staaf's government, and the subsequent Hammer-Sköld government allocated funds for the purchase of two more battleships of the same model.

However, left-wing political forces viewed this as interference by the king in politics, which is the prerogative of parliament, further strengthening their desire to reduce defence spending. Therefore, in 1926, the king lost this battle when the Right Party (today the Moderate Coalition Party) agreed to reduce defence spending. This marked the beginning of a decade of army cuts and reduced spending.

However, in 1936, probably noticing the German remilitarisation of the Rhineland, the government of Social Democrat of Per Albin Hansson immediately passed a new law, after which defence spending began to increase and the armed forces began to grow. The army, which at that time lacked a clear chain of command, underwent reorganisation. The subsequent events of the Second World War – in particular, the Soviet-Finnish Winter War and the German occupation of Denmark and Norway – proved this decision to be correct. Sweden during the Second World War. Neighbouring Norway and Denmark are occupied by Germany. Source: Johnny Öberg

Sweden during the Second World War. Neighbouring Norway and Denmark are occupied by Germany. Source: Johnny Öberg

In 1945, the Swedish Air Force had: 790 combat aircraft, and the Navy consisted of 7 battleships, 2 cruisers, 27 destroyer ships, 26 submarines, 42 minesweepers, 20 torpedo boats, 16 patrol boats, and 6 floating bases.

In the context of civil defence, each individual played an important role. Making the individual the central component of national security and ensuring their resilience was critically important, as Sweden had a fairly large territory but a relatively small population. Therefore, it was necessary to make the most effective use of every person in the event of an attack, and without the individual preparedness of every citizen, it would be difficult to achieve nationwide resilience and preparedness.

On the part of the authorities, civil defence aimed to inform the population about the threat and how to act in different situations, ensure evacuation and the functioning of shelters, the normal operation of emergency services, and coordinate the protection of infrastructure and industrial facilities.

Citizens were expected to be actively involved in the defence of the state and to be prepared to follow the instructions of the relevant authorities in the event of a crisis. According to the Civil Defence Act of 1944 (Government of National Unity, Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson), which applied to all men between the ages of 15 and 65, every household and a significant portion of private property, as tractors, trucks, livestock, and certain buildings, were assigned a specific role in the overall defence of Sweden. The civil defence system assigned approximately 230,000 citizens to various local and regional organisations, as well as another 65,000 citizens to factory defence organisations.

According to a 1943 government research report and the 1944 Civil Defence Act, civilians were to perform non-military functions, such as guarding businesses, fighting fires, clearing debris, assisting with evacuations, etc. – in other words, providing rear security.

At the same time, from 1942, mandatory military service existed for all men aged 18 to 47 (lasting 450 days), and reservists could be mobilised to participate in combat operations.

Territorial defence (Swedish: Hemvärnet) could also be involved in combat operations. Initially, these were various voluntary units that formed on their own, but on 29 May 1940, parliament passed a resolution legalising their subordination to the armed forces.

Civilians could acquire the necessary skills to protect their homes and businesses at state-run civil defence schools (Swedish: civilförsvarsskolor). In addition, by the 1940s, there were about 20 different voluntary civil defence organisations, comprising approximately one million citizens, and the government provided informational support for joining them, seeking to make this part of the collective culture.

Economic defence aimed to ensure the functioning of production, the distribution of critically important goods such as fuel, grain, medicines, and the distribution of weapons. In the context of economic defence, the Swedes relied on cooperation between the state and private companies, as well as on the use of their own raw materials for the manufacture of strategic goods.

While television companies and railways were state-owned, companies producing food, medicines, fuel, footwear, clothing and medical equipment were private. Such companies were granted the status of strategic enterprises in the event of war (Swedish: krigsviktiga företag, or K-companies) and entered into special contracts with the state, under which they operated as normal market players in peacetime, but in the event of war had to provide the state with a certain amount of products.

The mechanisms of cooperation between the state and private companies were clearly worked out, and the responsibilities of the parties were clearly separated. The state was responsible for storing products manufactured in peacetime. For such cooperation, companies were forced to adapt their organisation and production in accordance with economic defence plans, but it cannot be said that the need to cooperate with the state was disadvantageous for them.

Firstly, there was an understanding that if the Soviet Union invaded Sweden, free market trade for these companies would end. Secondly, being on the list of strategic enterprises allowed companies to count on the state's support if things went wrong, which proved to be true in the 1970s and 1980s.

In terms of the benefits for the state from such cooperation, in the 1950s and 1960s, Sweden was close to self-sufficiency in food, clothing and footwear (Autarky).

Another advantage was that these industries relied mainly on Swedish raw materials, which gave them greater independence in the event of war.

Psychological defence included combating enemy propaganda, ensuring the spread of official information and increasing the willingness of society to fight. To ensure the successful functioning of radio and newspapers in the event of war, secure locations were prepared for radio stations and publishing houses. Swedish Radio also prepared several radio recordings in case of an emergency.

However, the situation here was a little more complicated. Psychological defence included centralised, government-controlled channels of communication through the media, which led to criticism and accusations of excessive government interference, censorship and the use of this mechanism as government propaganda agencies.

The concept of total defence really took off with the start of the Cold War. Until the 1960s, nuclear war was seen as the main threat. But by the 1960s, the key challenge was a non-nuclear invasion by the Soviet Union.

At that time, Sweden had some things to counter such an enemy. Mandatory military service was already in place for all men aged 18 to 47, and at the peak of its armed forces' development, Sweden could field about 850,000 troops, of which about 110,000 would belong to the territorial defence.

As for the navy and air force, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Sweden had 33 large surface warships, 24 submarines and 50 air force divisions with 1,000 domestically produced aircraft. In the 1960s, two cruisers and 15 destroyers began to be gradually replaced by smaller but more powerful units.

However, in the 1970s and 1980s, Sweden's military power began to get worse: the defence budget for 1968-1972 was cut, leading to staff reductions, the cancellation of some training exercises and the postponement of equipment replacements. This was due to several factors. Firstly, in the mid-1960s, the socio-economic situation began to deteriorate and the left wing of the Social Democrats began to insist on savings at the expense of defence spending. Secondly, prices for better equipment began to rise significantly.

Thirdly, Sweden's political leadership believed in the success of the so-called ‘détente’ policy.

As of 1982, Sweden could still field 850,000 active and reserve ground forces, 48 ships, including 12 submarines, and 23-24 air force divisions. This was still not bad for a small country compared to the USSR, but it was already significantly worse than 20 years earlier.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Sweden's total defence system began to decline. Over two decades, the military strength of the Swedish land forces was reduced by 95%, and the naval and air forces by 70%.

In addition, 70% of all military bases were closed. In 2010, recruitment into the army in peacetime was abolished.

In terms of economic security, contracts with K-companies (then numbering around 11,000) were not renewed in the 1990s. The civil defence system was disbanded and partially reorganised to fit the new civil crisis management system, with a focus on non-military risks and vulnerabilities, and all general defence training and educational activities were discontinued.

Just as a result, the previous organisational structure was dismantled, and with it, the construction of new bomb shelters and the maintenance of existing ones was discontinued, evacuation plans were cancelled, and the early warning system for air attacks was dismantled.

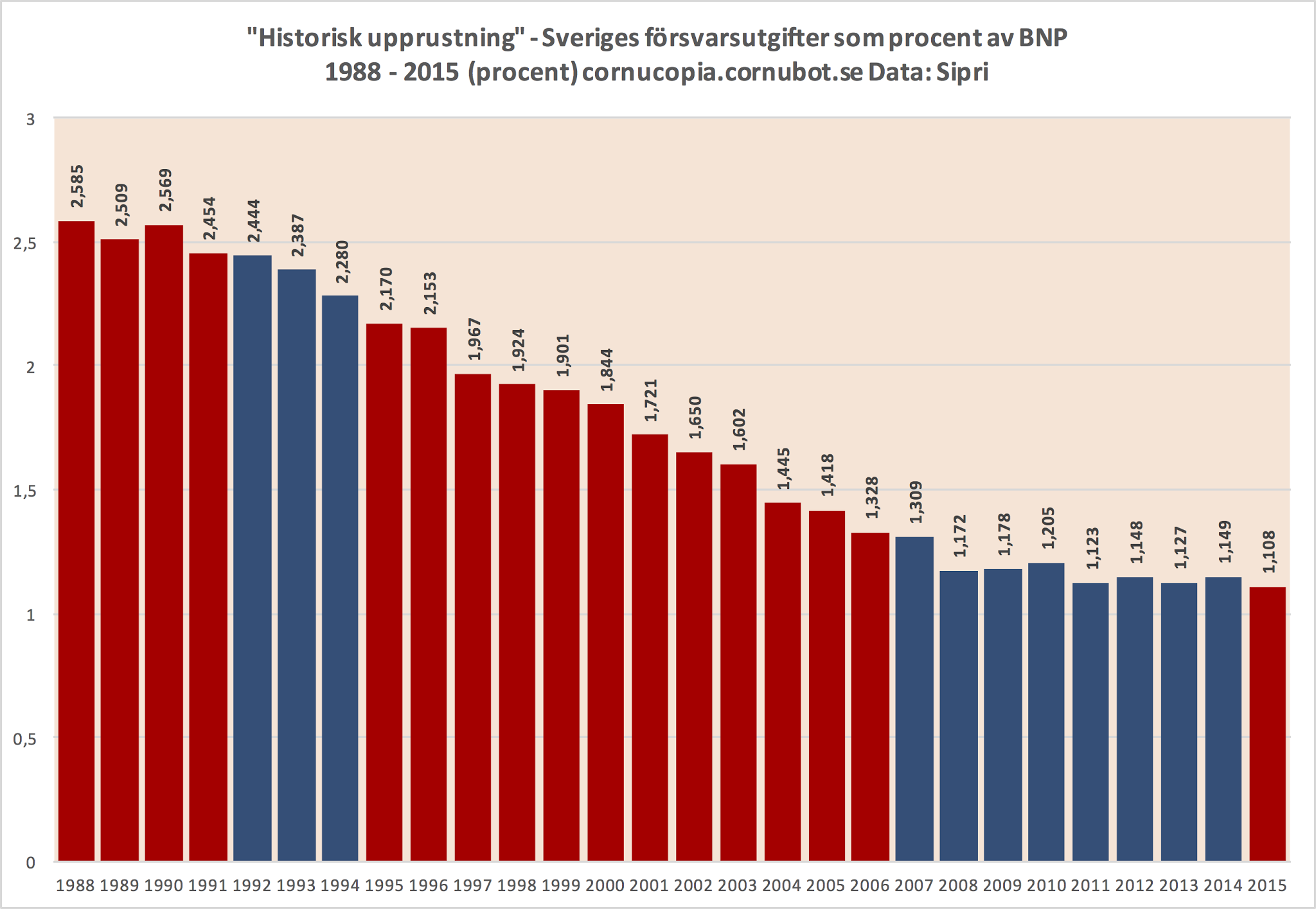

The total defence system was on the verge of disappearing. But everything changed with Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2014. Defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 1988-2015

Defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 1988-2015

A quarter of a century later, there was a need to restore total defence. But the world had changed significantly. Business and enterprises had become internationalised, and many of them had been privatised. Supply chains had become much more complex. There was a revolution in the information sphere (the internet appeared and developed). The composition of the population changed significantly. A phenomenon known as hybrid warfare emerged, and the armed forces and military infrastructure were no longer what they had been, even compared to the 1980s.

This state of affairs highlighted how much work needed to be done. In 2015 (under the coalition government of Prime Minister Stefan Löfven's Social Democratic and Green parties), a law/plan was passed that defined Sweden's defence policy for 2016-2020, which was both ambitious and revolutionary.

It was revolutionary because, for the first time in more than 20 years (since 2017), spending on the armed forces was increasing rather than decreasing, and there were plans to increase it every year. Five political parties agreed to abandon their defence policies and form a group of representatives from these parties to regularly monitor progress. Sweden has set a course to shift the priorities of the armed forces from international missions to national defence. A decision was made to increase the personnel of the armed forces and territorial defence, as well as to allocate resources to strengthen civil defence and voluntary organisations.

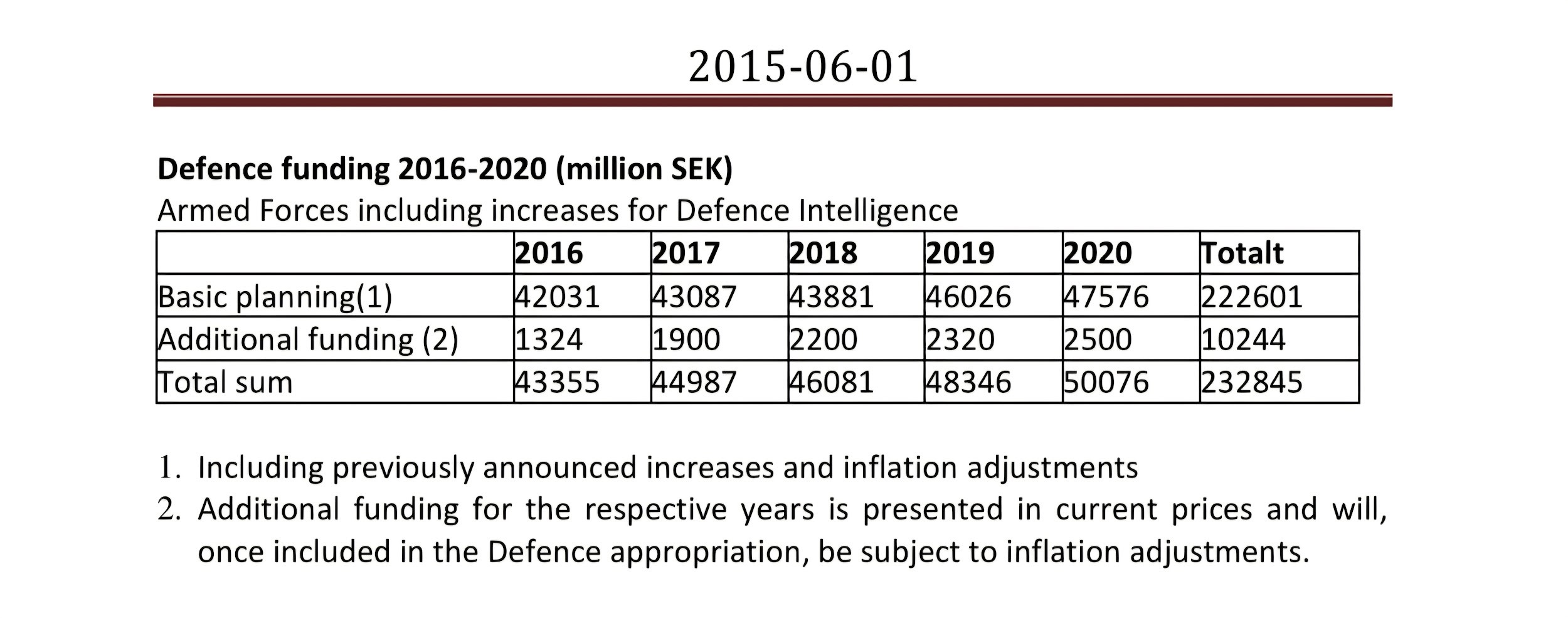

This was ambitious, as radical rearmament, modernisation of equipment, expansion and creation of new military units, and a complete reorientation of the army from international missions to national defence were planned within four years. Defence spending was laid out in a 2015 document that defined Sweden's defence policy for 2016-2020

Defence spending was laid out in a 2015 document that defined Sweden's defence policy for 2016-2020

In 2017, Sweden brought back conscription. According to the law, both men and women are subject to conscription. In 2020, the Total Defence 2020 military training exercises began, which were to last a year and involve all elements of society – from parliament and local municipalities to the Riksbank (central bank) – practising actions in various scenarios, from terrorist attacks to invasions by other states. However, due to the pandemic, some elements of the exercises were postponed.

An important aspect is that the Swedes are actively studying the experience of the Russian-Ukrainian war. While the 2015 law provided for measures aimed at waging 20th-century wars and planned to increase the size of the land forces, navy and air force, the 2024 report of the Swedish Defence Commission (Ulf Kristersson's coalition government) focuses on countering UAVs, the adaptation of civilian technologies for military purposes, the ability to counter Russian electronic warfare systems, and the establishment of effective mechanisms for mobilisation and countering Russian cyberattacks. And, of course, the report talks about continuing to increase defence spending.

But recently, the government has gone even further in terms of defence spending. According to a government document dated 15 September 2025, defence spending has been revised upwards until 2030 and is now expected to reach 2.8% of GDP in 2026, 3.1% in 2028 and 3.5% in 2030.

At the same time, some key aspects of total defence have changed since the Cold War. When it comes to civil defence, during the Cold War, civilians were assigned the sole role of providing a secure rear. But in 1994 (under Ingvar Carlsson's Social Democratic government), the Compulsory Total Defence Act was passed, which is still in force today. According to this law, citizens can be involved not only in civil defence but also in military defence (provided that their health allows it and after additional training) if the government decides so .

It is also noteworthy that the body coordinating civil defence – the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Swedish: Myndigheten för samhällsskydd, abbreviated MSB) – was removed from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Justice in 2022 due to lack of efficiency and transferred to the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defence. The position of Minister of Civil Defence, who reports to the Ministry of Defence, was also created. This can be seen as an additional sign of the changing role of civil defence: a shift from emergency situations to defence. A law has already been passed whereby, on 1 January 2026, the ministry will be renamed the Ministry of Civil Defence (Swedish: Myndigheten för civilt försvar – MCF), which should finalise this transition.

When it comes to psychological defence, it has also undergone changes: whereas previously it was a matter of centralised efforts by the authorities to counter disinformation, in the age of the internet, cyberattacks and information leaks, the responsibility for finding truthful information now rests with ordinary citizens.

However, this does not mean that psychological defence is now solely the responsibility of citizens. The current task of political leaders and defence institutions is to ensure that the population is capable and willing to participate in activities that strengthen their resilience and readiness to defend the country in the event of war. This concept is known as försvarsvilja – readiness or willingness to defend.

Psychological defence is coordinated and developed by the government through the Agency for Psychological Defence (Swedish: Myndigheten för psykologiskt försvar), which, in addition to promoting försvarsvilja, is also responsible for teaching Swedes to recognise disinformation and manipulation of information and how to counteract it.

In the context of military defence, Sweden's accession to NATO has also had an impact. Whereas previously the focus was on defending Sweden alone and by its own forces, Sweden is now part of a collective defence system that requires it to defend its allies, but also provides for the possibility of receiving assistance from them. Sweden in NATO. Photo: Helena Fahleson (Di)

Sweden in NATO. Photo: Helena Fahleson (Di)

Another change in the context of military defence can be seen in the change in the perception of how a conflict would begin. Whereas during the Cold War, a simple invasion by Soviet troops was expected, it is now expected that an armed attack on Sweden could be preceded by numerous and varied hybrid attacks over a short or long period of time.

However, the most significant change in this concept compared to the Cold War era is the change in the approach to the concept of ‘peacetime’. During the Cold War, peacetime was considered to be any time when a country was not at war and during which reserves were accumulated and actions were planned in case of aggression. Now, however, military and political leaders are convinced that although the country is not at war, it is also not at peace. This can probably best be described as a “state of non-peace”.

Sweden is already experiencing constant hybrid attacks from Russia (for example, recent damage to cables in the Baltic Sea, or cases where GPS suddenly stopped working), but their intensity could be either the enemy's ultimate goal (i.e., the enemy's first objective is to destabilise Sweden) or a prelude to armed conflict.

The 2022 Strategic Doctrine emphasises that the situation in the ‘grey zone’ may fluctuate between low intensity and open hostilities, creating uncertainty about the enemy's true intentions. Therefore, “peace” in the current context is interpreted rather as a conditional norm of instability, different from the traditional understanding of the Cold War era. This change is clearly evident in a recent interview with Swedish Commander-in-Chief Michael Claesson, in which he emphasises that Russia is already capable of attacking European countries and, despite all the problems in the armed forces, he is preparing for exactly that.

At the same time, despite the change in approach, in practice, things are not so good. For example, the armed forces lack qualified officers, and some of the officers are already approaching retirement age. In military education, military practice is often replaced by purely academic tasks. There are cases when, due to long-term planning of military procurement, equipment becomes obsolete by the time it reaches the military.

As for the shortage of personnel in the army, the government is already taking steps to solve the problem. As of 2025, the Swedish Armed Forces will have about 66,800 personnel, including 10,200 career officers, 6,900 career enlisted personnel and sergeants of all branches of the armed forces, 4,800 reservists in lower and middle ranks of all branches of the armed forces (part-time service) and 11,400 civilian employees. In addition, the Armed Forces include 5,800 reserve officers and 26,500 representatives of the territorial defence (Swedish: Hemvärnet).

It should be noted that although formally the number of officers in the Swedish army is relatively sufficient, there is a real shortage of combat commanders, as many officers are approaching retirement age. At the same time, even officers of pre-retirement age are valuable, as in the event of war they can be involved in administrative and training functions, as well as planning work in headquarters. Therefore, the government is currently considering raising the upper age limit for conscripting former officers from 47 to 70. In this way, the government seeks to increase the number of combat-ready personnel in the army through conscription, while older and more experienced officers will be able to train them and thus nurture a new generation of combat-ready young commanders.

The government also plans to gradually increase the number of recruits: 10,000 annually until 2030 and 12,000 between 2032 and 2035, so that in 2030 it will be possible, if necessary, to field an army of 130,000. In addition, there are plans to increase the salaries of soldiers, cadets and officer candidates from 2026.

However, there have also been successes: for example, political parties recently demonstrated that they are adhering to the agreement on the depoliticisation of the country's defence by quickly agreeing to allocate an additional 300 billion kronor (approximately 27 billion euros) to defence. The Swedish Ministry of Defence also recently presented the first domestic unmanned mini-submarine, which shows that the Swedes are trying to keep up with the times in terms of technology.

In terms of the amount of equipment, the approximate figures are as follows:

Land forces: approximately 110 Stridsvagn 122 tanks, which are planned to be upgraded to the Stridsvagn 123A standard (2027-2030), 26 self-propelled guns and approximately 6800 armoured combat vehicles, including Stridsfordon 90 (CV90). In addition, 44 new Leopard 2A8 tanks (Stridsvagn 123B) have been ordered, with deliveries expected in 2028-2031. The main battle tank Stridsvagn 122 (Sweden). Photo: overclockers

The main battle tank Stridsvagn 122 (Sweden). Photo: overclockers

Air Force: 90 Jas 39-Gripen fighters in C and D modifications (another 60 E modifications are planned to be received by 2030), 6 TP 84 Hercules transport aircraft, 2 S 100 D radar reconnaissance aircraft, 2 S 102 radio reconnaissance aircraft, 1 Boeing C-17 heavy transport aircraft, 2 aircraft for transporting senior state officials, 2 TP 100 aircraft that can be used for transporting personnel as for surveillance, 1 SK 60 training aircraft and about 50 helicopters.

JAS 39 Gripen of the Swedish Air Force at the air show in Kaivopuisto (Helsinki) in June 2017

JAS 39 Gripen of the Swedish Air Force at the air show in Kaivopuisto (Helsinki) in June 2017

Navy: 5 submarines, 7 corvettes, 9 minesweepers, 14 patrol boats. In 2027-2028, 2 more submarines are expected to be delivered. Thus, Sweden has 35 units of equipment in service, not counting small patrol boats.

Sweden is an example of a country with a systematic and comprehensive approach to national defence. As a non-aligned country throughout the 20th century, Sweden has developed an autonomous and self-sufficient security model that does not depend on the support of other states. Total defence is a social contract under which every citizen must take their place in the defence of the state.

Despite the problems with the reduction of armed forces after the Cold War, which were and still are characteristic of the entire Europe, including Ukraine, the concept of total defence is a qualitative response to today's threats, when the whole world is mentally preparing for World War III.

For Ukraine, the great war began in 2014 and is still far from over. Even after the cessation of hostilities, Russia, with its enormous human and material resources and imperial mindset, will pose a threat just as it does to both Ukraine and all of Europe. The Russian-Ukrainian war shows that even with powerful partners and allies, you should rely on yourself first and foremost, and others will only help those who resist.

The war has revealed systemic problems in Ukraine that are extremely important to solve. These are, first and foremost, organisational problems in the Defence Forces, problems with the mechanism for mobilising people and providing information to society. Ukraine also finds itself in a strategically dangerous position, surrounded by enemies in a semi-circle stretching from Brest in Belarus to the Black Sea and the temporarily occupied Kherson region, as well as facing threats from unrecognised Transnistria, the Russian-occupied territory of Moldova. Ukraine must therefore find solutions to these problems in order to survive.

In such a situation, Ukrainian citizens must become the central element of defence, and the state must ensure their resilience as much as possible. The defence of the state must become a social contract for all citizens.

Several important aspects can be highlighted: institutional unity of the civil and military components, participation of the whole society in the defence of the state, training and informing citizens.

When it comes to institutional unity, in Sweden, civil and military defence are coordinated within a single doctrine, which enables planning from the highest level of government to the smallest local municipality, so that everyone knows their role during a crisis. In Ukraine, however, many initiatives are still developing chaotically and under pressure from circumstances. In Ukraine, public involvement is quite strong, but it is often a purely voluntary initiative rather than the result of state mechanisms. The same applies to the involvement of private business in defence: while in Sweden companies participate in the planning of total defence in advance, in Ukraine individual businesses have joined on their own initiative.

Similarly, in the context of public participation in national defence, Sweden is working hard to encourage citizens to participate in various forms of defence. Take, for example, territorial defence (Hemvärnet): Hemvärnet's leadership is persistently building an image of ‘soldiers of society’, working to create a collective identity based on belonging to the organisation, and working hard to make joining their ranks an honour.

An important aspect that Ukraine should adopt is the education and information of citizens, or, in other words, the interaction between the authorities and society. While Sweden regularly communicates with its citizens on defence issues, for example through the publication of brochures entitled ‘If crisis or war comes’ (Swedish: Om krisen eller kriget kommer), in Ukraine citizens often learn about important issues from the media, sometimes from obscure anonymous sources, often mixed with conspiracy theories, which, on the one hand, makes the information provided to citizens less comprehensive and, on the other hand, increases the risk of citizens receiving distorted information and contributes to growing distrust of the state.

Second, it is worth noting Sweden's planning for war. Since the Cold War, Sweden has been preparing plans for food, fuel, medical supplies, population evacuation, and backup power supply systems. In Ukraine, all this was formed reactively, already during the war (generators, fuel, logistics for humanitarian aid).

Thirdly, the practice of training reservists during the Cold War: for decades, Sweden trained a reserve force that would serve as a source of reinforcement for the regular army in the event of war – and these would be trained people for whom ammunition and weapons had been prepared, which brings us back to the issues of strategic planning and stockpiling.

At the same time, Ukraine needs to establish and actively develop cooperation with countries in Europe and North America, as well as countries in other regions, to mutually strengthen their capabilities. First and foremost with the Nordic and Baltic countries, which face common security challenges, have experience of total defence and are acutely aware of the threat from Russia.

Kostiantyn Hlushko, staff analyst and reviewer at the "Resurgam" Center for Northern European Policy

You may be interested