INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL

COMMUNITY

+ Join

Support

Matviy Sukhachov, commentator on British politics, exclusively for Resurgam

President Volodymyr Zelensky met with the former Chief of the Defence Staff of the United Kingdom, Admiral Tony Radakin, and the new Chief of the Defence Staff, Richard Knighton, on August 26, 2025. Source: Office of the President of Ukraine

President Volodymyr Zelensky met with the former Chief of the Defence Staff of the United Kingdom, Admiral Tony Radakin, and the new Chief of the Defence Staff, Richard Knighton, on August 26, 2025. Source: Office of the President of Ukraine

The United Kingdom has been a key partner for Ukraine since 2014, when Russia launched its invasion. London's military and diplomatic support has often been more decisive and brave compared to other countries. And after the start of Trump's second presidency, which weakened support for Ukraine, Britain took the lead in coordinating aid for Kyiv. Ultimately, the United Kingdom is the main driver of the so-called ‘Coalition of the Willing’ – an alliance of countries that can commit to supporting Ukraine’s security after the war.

Well, is Britain willing enough? Not only to help Ukraine, but to directly guarantee its security after the war?

A group of countries called the ‘Coalition of the Willing,’ which pledged to support Ukraine in its war with Russia, was officially established on 2 March 2025 on the initiative of British Prime Minister Keir Starmer during a summit in London. The term ‘coalition of the willing’ is well established in international relations and refers to a temporary international partnership created to achieve a specific goal, usually of a military or political nature. Summit of European and EU leaders in London, 2 March 2025. NTB/Javad Parsa/via REUTERS

Summit of European and EU leaders in London, 2 March 2025. NTB/Javad Parsa/via REUTERS

In Ukraine, two translations of this concept are used – “coalition of the decisive” and “coalition of the willing” – which causes confusion. According to Alona Getmanchuk, the newly appointed head of Ukraine's Mission to NATO, the drivers of the coalition, Britain and France, as well as other participants invited by them to relevant meetings, refer to themselves as a ‘coalition of the willing,’ following established terminology in international relations. The leaders of the “coalition of the willing” differ from the “coalition of the decisive” primarily in the fact that they call themselves a “coalition of the willing” and seek to involve a wider range of participants than is necessary for swift and decisive action.

According to Alona Getmanchuk, in the Ukrainian case, it is more than a classic “coalition of the willing”. It is a coalition that can do much more and move much faster than the G7, the EU, and NATO, ignoring Putin's “red lines”. ‘Such steps require not only a willingness to support Ukraine, but also a demonstration of the appropriate level of decisiveness. Since the most decisive and ambitious step, at that time, seemed to be the very possibility of sending troops from these countries to Ukraine, the coalition of the decisive quickly became associated with countries that were ready to do so,‘ Getmanchuk writes. That is why, in this article, we will give preference to the translation ’coalition of the decisive."

On 10 April 2025, at the first meeting of defence ministers of member countries within the framework of the ‘coalition of the decisive’, four key objectives of the alliance were announced by British Defence Secretary John Gilley: ensuring a secure sky, a secure sea, peace on land, and support for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as the main factor in deterring Russian aggression by providing comprehensive assistance to Ukraine. The fact that such statements were made by London indicates that it is the British who are behind the active development of the “coalition of the decisive.”

John Gilley also outlined ways to achieve the coalition's goals: the possibility of deploying international security forces on the territory of Ukraine, supporting Ukraine in the negotiation process, sending a peacekeeping contingent from coalition member countries, etc.

Britain often organised summits of the ‘coalition of the decisive’ in its own country, as well as in the format of online meetings, which brought together not only the leaders of the coalition member states, but also various members of the governments of these countries (mostly defence ministers and foreign ministers). Although the meeting of the “coalition of the decisive” on 10 July 2025 took place in Rome, it was chaired by Britain, which acted as the organiser.

London is trying to attract more countries to the “coalition of the decisive” – especially the US, which is trying to distance itself from European problems. Thus, American representatives appeared for the first time at the same coalition meeting in Rome: Donald Trump's special representative Keith Kellogg and Senators Lindsey Graham and Richard Blumenthal, who are the most pro-Ukrainian American politicians. Trump himself joined a telephone conversation between the countries of the “coalition of the decisive” that gathered in Paris on 4 September.

As we can see, Britain plays a leading and organisational role in the “coalition of the decisive”, but at the same time fulfils its obligations to Ukraine in accordance with the coalition’s goals. This mainly concerns providing Kyiv with financial and military support, as well as the potential deployment of military contingents to Ukraine. Thus, at the beginning of the coalition's creation, Starmer announced an agreement with Ukraine under which London would finance the purchase of more than 5,000 air defence missiles for Kyiv at a cost of £1.6 billion. Another important commitment that Britain fulfilled, together with other European governments, was the supply of long-range missiles to Ukraine, which was announced after the summit on 4 September.

The most controversial topic, which is periodically discussed within the “coalition of the decisive,” concerns sending military troops to Ukraine. Back in February 2025, Starmer confirmed the possibility of sending British troops. As a result, this issue has grown into a separate major political debate, with more and more parties agreeing that the presence of a foreign military contingent in Ukraine would be a reliable guarantee of security.

On 10 July 2025, Defence Secretary John Gilley reaffirmed the UK's readiness to deploy troops to Ukraine. He added that, together with French and other soldiers, the number of military personnel on Ukrainian territory would be approximately 50,000, and that the US would be ready to support this plan.

On 20 August 2025, after a meeting between European leaders and US President Donald Trump in Washington, Chief of the Defence Staff Admiral Tony Radakin gave more details about the idea of a military contingent. He outlined the main difficulties that, in his opinion, could force the government to abandon the idea altogether.

Firstly, he stated that Britain would only be prepared to send troops to rear areas to protect critical infrastructure, train Ukrainian fighters and monitor security in the country. According to Radakin, foreign troops on the front lines would become a direct target for Russia, which could escalate the situation and provoke a response from the West.

Secondly, another reason for the delay in making such a decision, according to Radakin, is the position of the United States. More precisely, the need for consensus with the United States on sending troops to Ukraine or equipping them. After a meeting in Washington on 18 August, Trump refused to send peacekeepers to Ukraine, but seems willing to provide air support for the European contingent.

Obviously, the decision on the deployment of a military contingent will be difficult (or even impossible), and its outcome will be insufficient for Ukraine's security due to a number of primarily political constraints.

While the prospect of sending British troops to Ukraine remains unclear, the commitment to produce weapons for Ukraine is much more realistic due to lower risks. Britain is already one of the countries investing most heavily in the Ukrainian defence industry.

The first major agreement was a defence pact signed between Britain and Ukraine on 8 April 2024. This agreement was the first step in implementing the corresponding provisions of the Security Cooperation Agreement signed between the countries at the beginning of the year, which provided, in particular, for the facilitation of defence-industrial cooperation, joint production and technology transfer. This agreement was groundbreaking in strengthening relations between London and Kyiv, as Ukraine could not only import weapons but also establish domestic weapons production with the support and investment of Western companies. Starmer and Zelensky in front of one of the drones built in Ukraine with financial support from the UK, 16 January 2025. Source: Efrem Lukatsky/AP Photo/picture alliance

Starmer and Zelensky in front of one of the drones built in Ukraine with financial support from the UK, 16 January 2025. Source: Efrem Lukatsky/AP Photo/picture alliance

An important agreement on the joint production of drones by British companies was signed on 24 June 2025. According to the agreement, drone production will continue for the next three years. London will finance the purchase of a wide range of Ukrainian drone models, which will be jointly produced in the UK, after which all drones produced will be sent to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. After the war ends, the drones produced will be distributed between the United Kingdom and Ukraine. Also, according to the agreement, Ukraine will transfer data from the front line on the operation and effectiveness of the drones.

In general, there are many such different defence-industrial agreements on the production of weapons in Ukraine. However, another question is whether the British will remain just as eager to help Ukraine with weapons production after the war ends? Various restrictions could weaken military-defence cooperation, in particular the potential rise to power of the Reform UK party, which is not sympathetic to Ukraine.

But so far, there are no alarming signs of a weakening of military-industrial cooperation. Moreover, on 16 January 2025, Zelensky and Starmer signed an agreement on a 100-year partnership between Ukraine and Britain. The Ukrainian Parliament ratified the agreement on 18 August, although the British Parliament has not yet done so. In particular, in terms of defence-industrial cooperation, the agreement provides for the rapid, innovative and sustainable production of weapons and ammunition, the provision of annual military aid to Ukraine in the amount of at least £3 billion per year, and the identification of mutual military needs (including the deployment of military bases and support for defence infrastructure on the territory of Ukraine).

After reviewing several examples of security commitments and potential security guarantees that Ukraine could receive from the United Kingdom after the war, a key question arises: will London be able to implement them? There are several limitations that could stand in the way.

Firstly, the political situation in the United Kingdom is tense due to economic and migration issues. If, on the wave of public discontent, the right-wing populist Reform UK party comes to power, it is very likely that Britain's potential role in the Ukrainian security model will diminish, which will generally undermine the ‘coalition of the decisive’. In general, participation in the coalition is based on an unstable situational consensus, which could easily be shaken if there is a change of power in one or more participating countries.

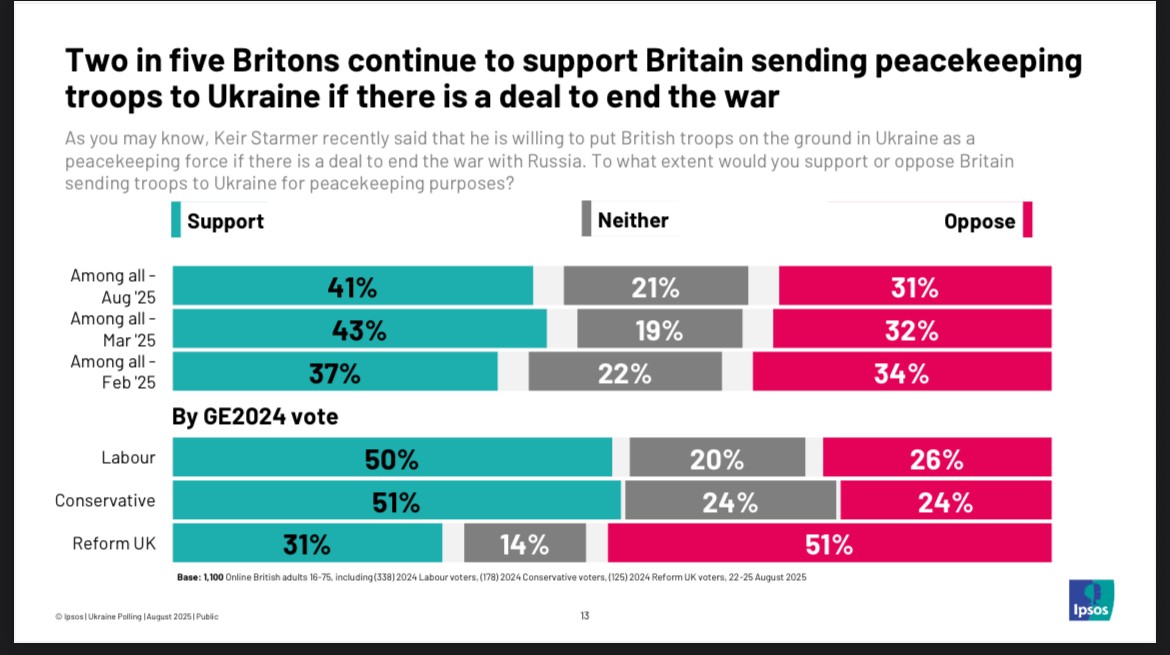

The British themselves have conflicting views on sending their troops to Ukraine. According to an Ipsos poll (15 September 2025), 41% of Britons support such a decision, although in March this year the figure was 52% (YouGov poll). However, 55% of Britons generally support the United Kingdom giving Ukraine security guarantees similar to those provided by NATO. Two out of five Britons continue to support sending British peacekeeping forces to Ukraine after an agreement to end the war. Source: Ipsos

Two out of five Britons continue to support sending British peacekeeping forces to Ukraine after an agreement to end the war. Source: Ipsos

The second problem is the participation of the US, which is needed by the ‘coalition of the decisive’. US support will be necessary even if Washington refuses to provide its troops. This includes assistance in mission planning, logistics, intelligence and the provision of additional weapons. For example, on 20 March, Armed Forces Minister Luke Pollard stated that Britain would not send peacekeepers to Ukraine without US support. It is unlikely that Britain has become more decisive on this issue, although Trump may still be willing to involve the US in this matter to a limited extent.

The UK's ability to provide security guarantees to Ukraine is hindered by the reduction of its armed forces and the need to increase defence spending.

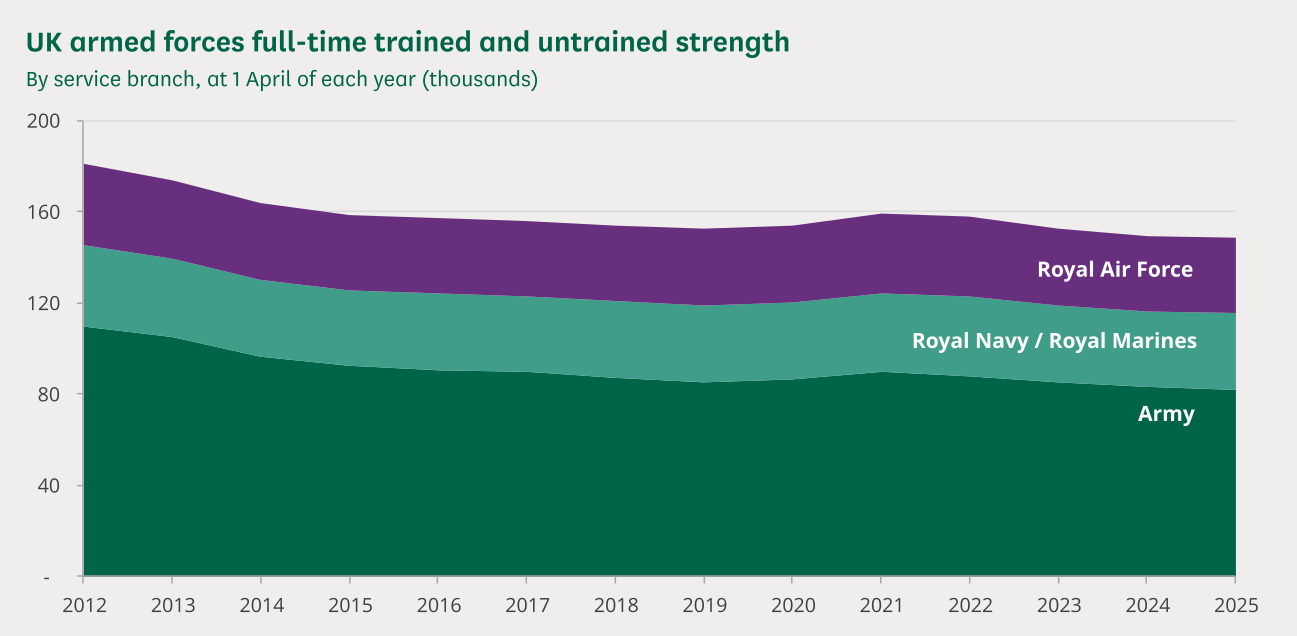

As of 1 April 2025, the total number of permanent personnel in the UK armed forces (trained and untrained) was approximately 147,300. All three branches of the Armed Forces are below their target levels: The Infantry is 3% below target, the Navy and Marine Corps are 8% below target, and the Air Force is 13% below target. Overall, the strength of the British Armed Forces was 8,590 (6%) below target. In 2024/25, the total number of personnel decreased: 1,140 more left the service than joined it. In the previous year, the net reduction was 4,430. The Ministry of Defence said it was facing a ‘staffing crisis’ due to ongoing problems with recruitment and retention. The key question is: can the UK send troops to Ukraine which it lacks itself? This is in addition to the fact that Britain, as well as any other European country, needs to rearm.

In February 2025, the think tank "UK in a Changing Europe" stated that the UK was ‘unprepared for a long-term conflict,’ despite the fact that from 2014 to 2023, the country consistently spent more than 2.1% of its GDP on defence, with the sixth largest military budget in the world (£53.9 billion in 2023/24). In February, Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced an increase in UK defence spending to 2.5% of GDP till 2027 and to 3% during the next parliamentary term. UK Armed Forces: full-time personnel (trained and untrained) as of 1 April (in thousands). Source: House of Commons Library

UK Armed Forces: full-time personnel (trained and untrained) as of 1 April (in thousands). Source: House of Commons Library

The UK is experiencing a serious fiscal crisis, which may limit the level of support for Ukraine in the future. In the 2024/25 financial year, the UK budget deficit was £148-152 billion (5.3% of GDP), £20.7 billion more than in the previous year. And this year, the situation is even worse. In June 2025, the UK borrowed £20.7 billion, the second highest figure for June since monthly records began in 1993. Public debt reached 95.8-96.3% of GDP in mid-2025, the highest level since the early 1960s.

Ultimately, even while in debt, the UK is helping Ukraine, demonstrating its incredible commitment to our country's security. However, any problems in the country that is our greatest ally are not in Ukraine's interest. The current political, military and financial problems in the UK, despite the relatively strong consensus among the British on the need to support Ukraine, may limit London's role in the Ukrainian security model. In turn, insufficient deterrence will increase the likelihood of another Russian invasion – and not only into Ukraine.

Britain must continue to fund Ukrainian defence and send weapons to Ukraine. Britain must continue to cooperate with Ukraine in the defence industry sector. Britain must continue to be a leader in shaping Ukraine's security infrastructure and bring together other countries around the world that are willing to participate in this. Britain must find the decisiveness it needs to guarantee Ukraine's security.

You may be interested